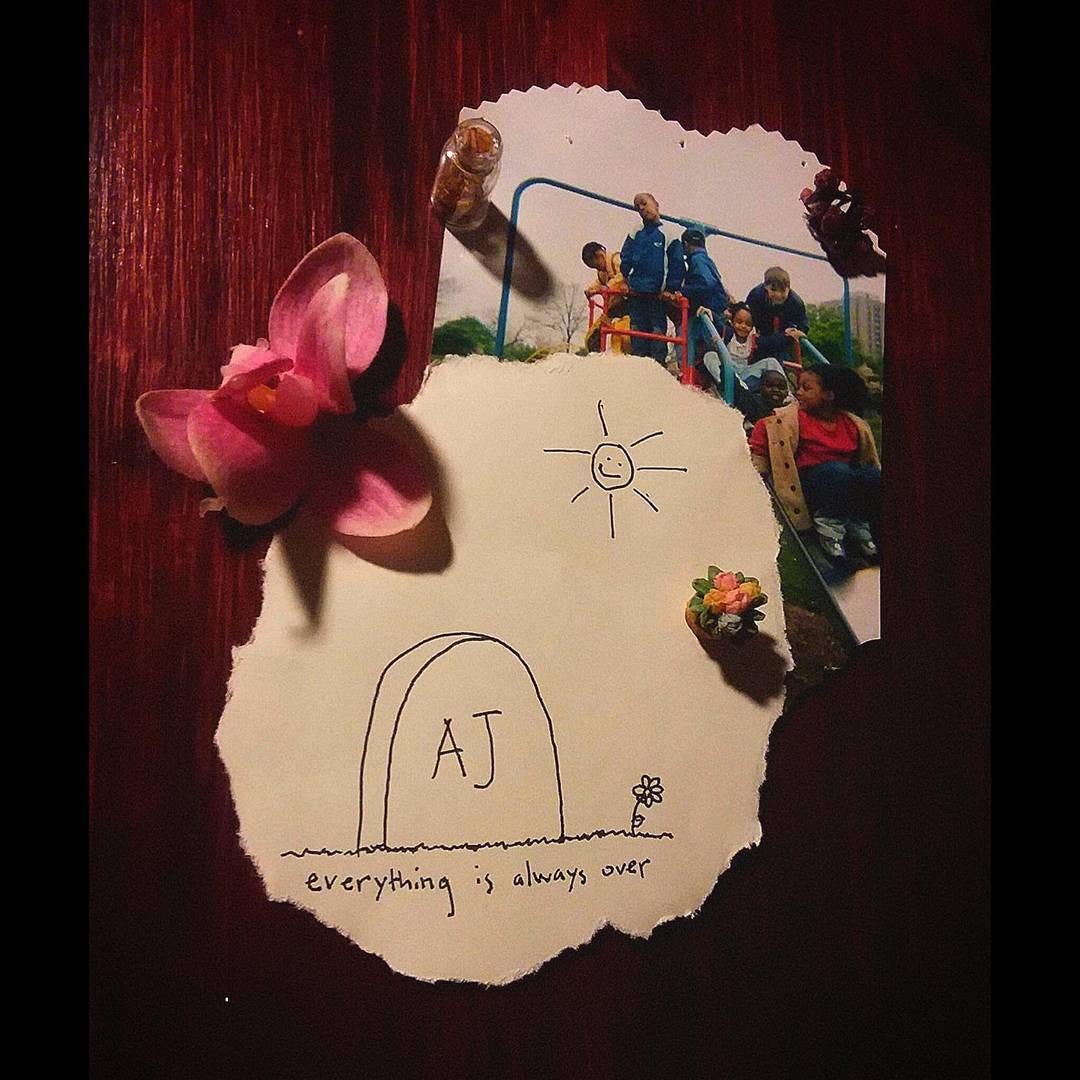

Aiyana Mo’nay Stanley-Jones is dead and she needs our help

A little girl pouts in her pink pajamas, sitting on the floor, surrounded by colorful chalk drawings. We’re sitting on the floor with her, coloring rainbows and hearts and stars and flowers with our pieces of chalk.

Her name is Aiyana Mo’nay Stanley-Jones. She is seven years old. Pink is her favorite color. She is clutching a white teddy bear; he’s her best friend, named ‘Mr. B.’

Next to Aiyana is a plain white wooden box, its lid open.

Is it a casket or a toy chest?

“Let’s play a game,” she says. “I’ll throw you the ball, and you tell me what you would do if you were free.” She tosses a smiling yellow ball into the crowd.

Aiyana Jones (played with tragic gusto by Triana Jackson, currently a junior at NYU) does not understand where she is: this strange, dark, purgatory-like place. She thinks she is late getting home. She promised her mother she would be home before the street lights came on. And “home is safe, home is safe,” she cries to herself. But her home wasn’t safe, not that night in Detroit. Not the night she was killed while sleeping on the couch during a police raid gone wrong. Aiyana Jones, seven years old, was shot in the head by a police officer’s gun. I see a flash, then hear a shot, then a scream pierces the air.

But Aiyana doesn’t know she is dead.

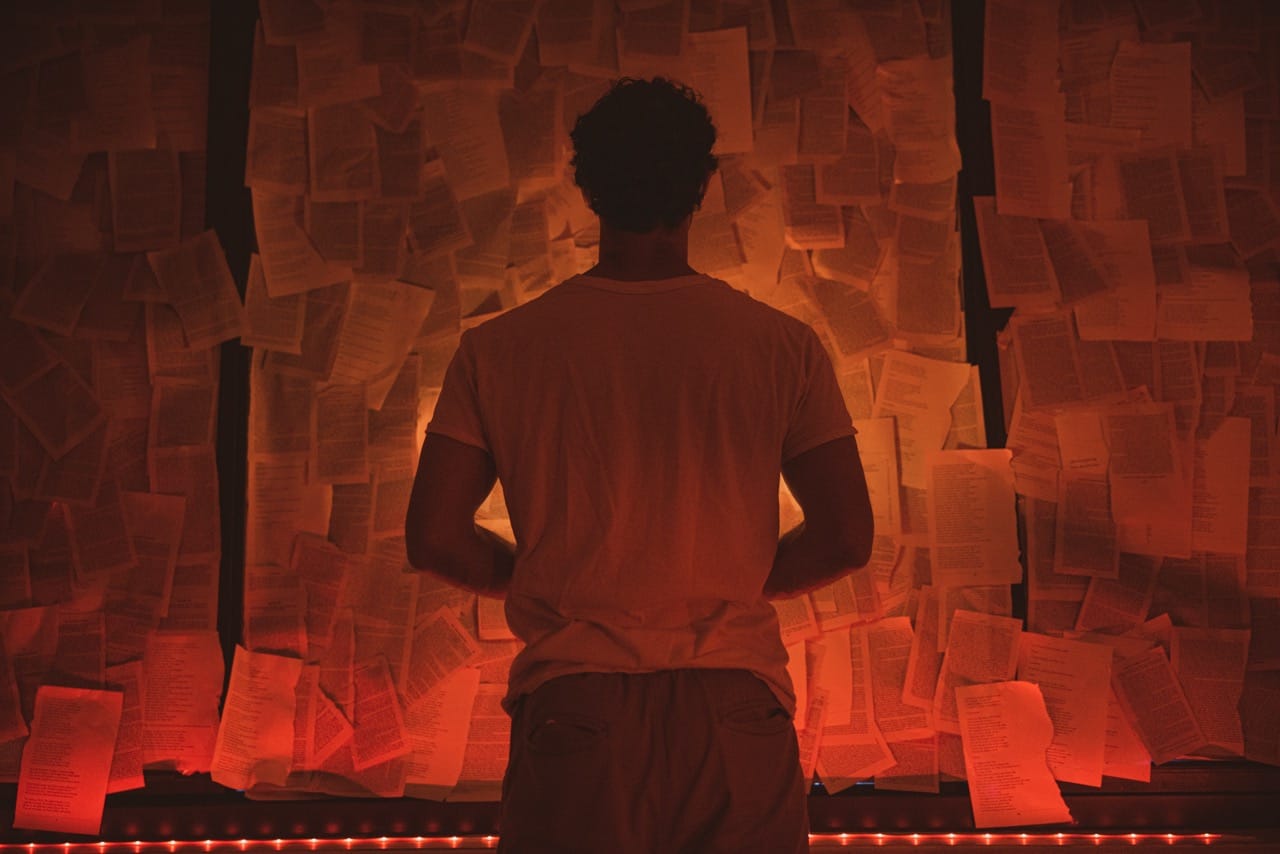

She is surrounded by four other African-American children (also played by a few NYU students/alumni). Three girls and one boy. The boy is not wearing shoes. All the children are all clad in tattered white clothing. They are the guardians of this in-between space filled with toys. A hula hoop sits on the floor next to an abandoned jump rope. There are Legos and Barbie dolls everywhere. One of the guardians smiles as she hands me a drawing she made. The sole purpose of this space is to guide the new ones into understanding where they are, because only with this knowledge, they may pass through, they tell us.

“We can see into all your memories,” they explain to Aiyana.

We do not learn their names.

Letters in the Dirt, created by Rosie DeSantis, acts as both a childhood game and a funeral at the same time. This kind of experimental theatre feels both timely and necessary: it is profound, moving, and gripping.

The guardians of this space ask Aiyana to play a guessing game. Each person in the audience picks an object from a basket, to try to trigger her memory.

Eventually, the entire room is asked to participate.

“You gotta be gentle,” counsels one of the ensemble members.

“Like you’re carrying an egg. Gentle.” She cradles her arms to demonstrate.

Get Kathryn Yu’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

SubscribeSubscribe

“Yeah! We’re the egg-carriers.”

In turn, we each pick an object and ask Aiyana, “Do you remember this?” It might be a cell phone or a Big Bird coloring book or a pair of tennis shoes. Sometimes she answers no, sometimes she tells us about the object, and sometimes she refuses to answer at all. Often, the answer is traumatizing for her. It’s a guessing game she doesn’t want to play, because each time, she remembers something else, something new about that night. At one moment, she turns away. She is hesitant to relive a particular scene but is slowly coaxed into describing the memory. It’s a happy one. Aiyana walks us through the memory of going to church one Sunday and listening to a gospel choir singing ‘Lily in the Valley.’ The members of the choir are all wearing those same pristine, white robes. The ensemble of guardians forms a line in front of us and begins singing, a capella.

There’s a lily in the valley (in the valley)

Bright as the morning star

“What is God like?” Aiyana asks.

There is a lily in the valley (in the valley)

Bright as the morning star

“Is God like when you put a whole lotta something big into something small? Is that it?” she wonders.

There is a lily in the valley (in the valley)

Bright as the morning star

“Did God create us because he had a whole bunch of sadness and needed somewhere to put it?”

Amen, amen, amen

Aiyana looks fragile and small. She loves the music because to her the sound feels like sadness and happiness and a bunch of other emotions, all mixed up at the same time. She beams, listening. I hear the four angelic voices in front of me. And as they sing, I think to myself there must come a reckoning soon — for the victims of police violence, for their families, for their communities, for all of us — that there is something wrong with us as a people. And there is something deeply rotten in this country because Black Americans are 2.5 times as likely as white Americans to be shot and killed by police officers. But when? When will we acknowledge these grave injustices? When will we be able to change?

I don’t know the answers.

There’s a cardboard sign in the room. It reads “BLM.” A cast member quietly pours blood from a mason jar onto it.

The lid clatters to the ground.

At the end of the show, the house lights come up and we, the audience, don’t know what to do. We sit in stunned silence, unsure if applause is the right move. Or is there is even a correct response at all. A woman in the audience gets up. She’s brought flowers tonight. She places a single pink flower on the floor, next to the white wooden box in remembrance.

Aiyana would have turned 15 years old this year. That night, we remembered her. I will continue to remember her, always.

And I will say her name.

Letters in the Dirt continues through December 9 at The Tank in New York City. Tickets are $13.

No Proscenium is a labor of love made possible by our generous Patreon backers: join them today!

In addition to the No Proscenium web site, our podcast, and our newsletters, you can find NoPro on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, in our Facebook community EverythingImmersive.com, and in our Slack community.

Discussion