Musings on NYC’s immersive past, present, and future

This is my last post as the NYC Curator of No Proscenium.

Starting with the first December newsletter issue, No Proscenium’s Associate Editor Kathryn Yu will take over as NYC Curator. You know her. You’ve read her reviews, you’ve met her at shows, you’ve enjoyed her curation on Instagram and Twitter, and seen her engage with the NoPro community. She will serve you as NYC Curator better than I can. Not only because she’s better fitted to what No Proscenium is turning into, but because on February 3, I’m leaving New York City.

Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about my experience of immersive in New York City. There are reasons why it is the gateway for immersive work emerging on the North American scene. New York City is the only truly cosmopolitan city in the United States. It has a direct lineage to the avant-garde work, installation art, and British/European theatre that led to Punchdrunk developing its techniques. New York City also has a dedicated audience of theatre stalwarts and tourists that can develop and maintain an audience for this sort of work. That’s all true. But for me, there’s something else.

New York City is a city of portals.

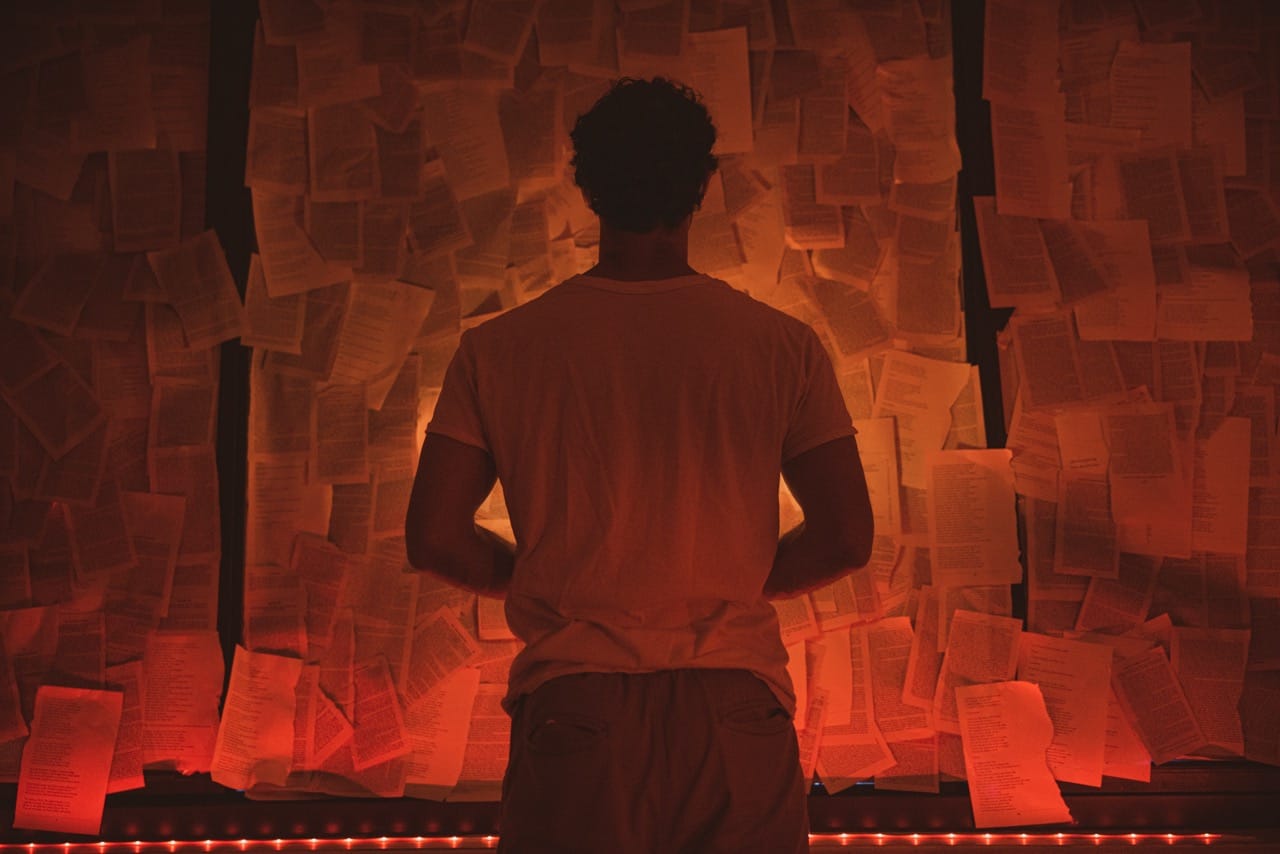

At one point in Linked Dance Theatre’s Like Real People Do (light spoilers follow), the audience is standing on a sidewalk on Christopher Street, across the street and down the road from the Lucille Lortel Theatre’s proscenium stage.

It’s far past dusk. The couple in the piece, Lauren and Oliver, are kissing beneath a streetlight. She’s pushing him against the red brick wall of an apartment building. They’re kissing with their bodies, romantic and intimate. But those of us in the audience aren’t looking at the kiss. We’re looking at the context, because long ago, on the other side of Manhattan, the performers pulled us through a portal. We aren’t just in New York City. We’re in the New York City of Lauren and Oliver’s relationship, where every crossroads is haunted by some memory.

We first met them on St. Mark’s Place. Then we followed them through the crossroads at St. Mark’s Place and Avenue A into Tompkins Square Park. They had their first kiss at this crossroads, started their relationship on their way to Astor Place, had their first fight in Washington Square Park, and by the time we got to Christopher Street, a few blocks and a few months (or years) later, their love had cracked, and they kissed with all the desperation of two people trying to force intimacy out of broken hearts. That streetlight, haunted forever by another world.

All of New York City is like that. A crossroads at every corner of the grid. Every inch of Manhattan is so drenched in history we cannot escape. We pass through portals all the time. The question isn’t whether or not you’ll be transported to another place, or reframed into another history. The question is whether or not you’ll notice when it happens.

It happened to me in 1997.

I was an undergraduate student at NYU Tisch School of the Arts, and I remember the profound dissatisfaction I felt at almost every play I saw. I was just some kid from downtown Richmond, California, a student at a stolidly conventional dramatic writing program, and I just didn’t know what was out there.

But a portal opened. A woman I worked with at Shakespeare and Co. Booksellers knew (from our conversations as we straightened the shelves in the store) about the kind of weirdness I yearned for: invisible secret societies, guerilla theatre companies bent on system disruption, self-made magic to awaken cities — all of the things I never achieved — and she said she had just the thing for me, some kind of high weirdness in DUMBO, which at the time was a strange and distant borderland.

It turns out the piece was Michael Counts’ Field’s of Mars, an immersive promenade piece with high audience agency in a 20,000 square foot warehouse. This is 1997, two years after Felix Barrett saw Robert Wilson’s immersive installation H.G. in the vaults of the old Clink Street prison near London Bridge. That experience led Barrett to create Woyzeck in 2000, Punchdrunk’s first production. That’s three years after Field of Mars. So immersive credentials: locked.

Field of Mars lives in my memory like an intense, fractured dream. One image haunts me often: a young woman in a soft cone of light. In my mind’s eye, she looks like Coquelicot from The King of Hearts, or maybe Columbine from the Invisibles. And she’s singing. I can only remember the refrain. She sang it like a Baroque hymn, like the trill top of glory at the height of a Bach motif, over and over again: “Glorious, so glorious! So glo-ri-ous!” And every time the refrain returned, my friend and I stepped closer together and closer to the singer, all at once.

The performer was Obie Award-winning performance artist Cynthia Hopkins. The song was her “Homage to Drink” from Gloria Deluxe, released in 1999. Have a listen, and while you do, imagine you’re in a 20,000-foot warehouse space, with extraordinary performances creeping out of the darkness all around you. Imagine you’ve never heard the phrase “immersive theatre” and you’ve never seen Sleep No More and all you know is that what you’re experiencing is glorious, so glorious, so glorious.

At the time there was very little context to understand Field of Mars. Not just for me, some half-drunk theatre kid on what turned out not to be a date, but also for New York Times reviewer Peter Marks. He had no idea what he’d just experienced. Reading his review of Field of Mars is like reading a classically trained art critic struggling with cubism in 1909, or a TV reviewer in 1990 lurching through a review for “Zen, or the Art of Catching a Killer.” Marks doesn’t even have the word “immersive” to contend with.

“Immersive” has long since lost the shock of the new. The kind of hand-wringing Noah and I went through on our first podcast together has melted away. The debate over whether or not immersive theatre is here to stay, or an expression of the zeitgeist, or a just a buzzword of the moment has faded away. Even the use of “immersive” as a marketing term for everything from themed parties to novels has died down. Nowadays in New York City, immersive work is a set of tools, or an approach, or just another part of the always-evolving performance vocabulary. It has stabilized and become part of the broader field of performance.

Sleep No More could run forever and has started to feel pretty dusty. Then She Fell could also run forever and still feels as intimate as it ever did, but its impact no longer sets the compass. The Great Comet played on Broadway to great artistic success, but very little comment with regards to its immersive elements. Neil Patrick Harris and Randy Weiner are putting together an immersive theatre project and somehow nobody really seems to care very much. Articles on what immersive is or where it’s going or is it scary/weird/uncomfortable to do just don’t come out anymore.

Instead, the non-profit off-Broadway world — the artistic establishment of NYC — is embracing immersive projects. Then She Fell and Sleep No More are functionally independent of the NYC non-profit theatre scene. One is a true indie and one is a commercial venture. Now that the immersive toolkit has been ingested by the New York City theatre world, non-profit off-Broadway houses can shuffle immersive work into their seasons with little fanfare. In the lead on this movement is the fearless producing body at Ars Nova, who has collaborated with The Woodshed Collective (KPOP), Andrew Hoepfner (Houseworld, Whisperlodge), and Kenny Finkle (UR STAR), among others.

There are still some folks using “immersive” as a word to describe large-scale themed parties or parties with art installations. But there are also promoters that use the toolkit of the large party in equal measure with the immersive theatre toolkit, events like the You Are So Lucky parties, N.D. Austin’s continuing speakeasy events, and Cynthia von Buhler’s Illuminati Ball.

This stabilization is good. The term melting away as a focal point is useful. The folks who make this stuff have been there for a long time. It means that the real work, like the work being done by No Proscenium editor-in-chief Noah Nelson’s League of Experiential & Immersive Artists (LEIA) initiative, can begin. Now is time for the practical work of boots on the ground. We can now address more important questions like space, legality, accessibility, and inclusivity.

Me, I want to see what the immersive world is like outside of North America. So in February, I’m heading to South America for a year. Let’s see what the flavor of immersive art is like in Medellin and Lima, in Buenos Aires and Santiago.

It’s difficult to leave New York City. New York City is a city of portals. Every crossroads seems like a gate to some new eddy of history. Every step you take could transport you to another place. But you’re always here, within the border of this enormous city of the world. New York City is so many places, all at once, that until you find the one portal that’s just for you — or that one portal you create yourself — you can’t quite get anywhere at all.

So it’s important to understand these guardians of the gates. These immersive theatre artists who have taken us through their portals. Andrew Hoepfner and Melinda Lauw. Erin Mee. Jennine Willett and Zach Morris and Tom Pearson and Elizabeth Carena and Tara O’Con. Kendra Slack and Jordan Chlapecka.

And Noah Nelson.

Thanks, man.

And you, you lucky folks, you’ve got Kathryn Yu to take care of you now.

Zay Amsbury is No Proscenium’s Curator at Large. You can follow him on Twitter at @zayamsbury.

Good luck, friend, and godspeed.

No Proscenium is a labor of love made possible by our generous backers like you: join them on Patreon today!

In addition to the No Proscenium web site, our podcast, and our newsletters, you can find NoPro on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, and in our online community Everything Immersive.

Discussion