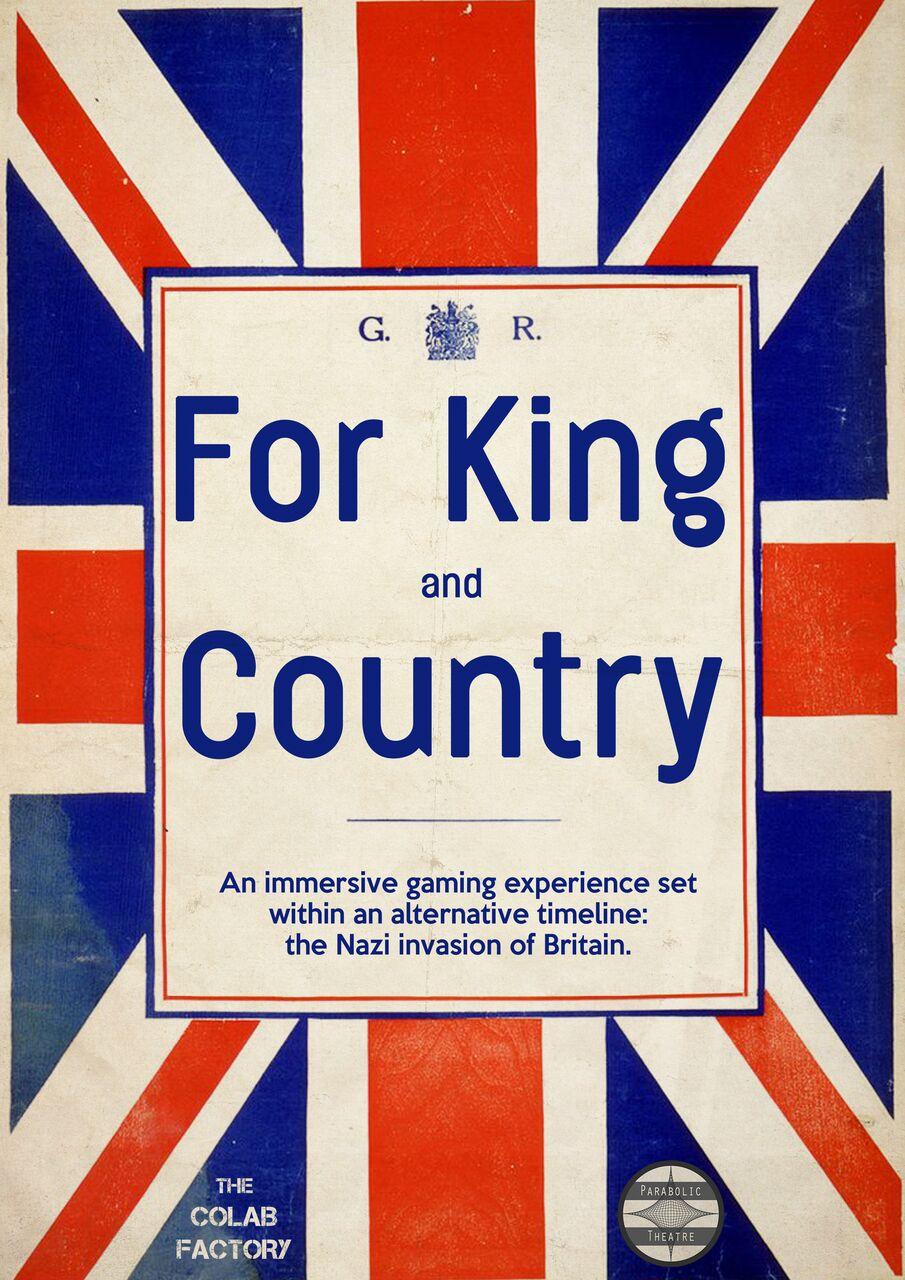

Live through ‘The Darkest Hour’ with Parabolic Theatre & Bedouin Shakespeare Company

It’s a mild spring evening in the neighborhood just south of London Bridge. A short walk from the hustling cultural hub of Borough Market lies a quieter but no less urban environment which serves as home to the CoLab Factory. A stripped-down warehouse-cum-reclaimed-space now serving as a theater, the Factory plays home to an ever-rotating crop of fresh productions by some of the United Kingdom’s finest emerging interactive and immersive producers. Parabolic Theatre, the current resident and developer of For King and Country, is headed by artistic director Owen Kingston, who is also employed as the venue manager for the Factory. A collaboration based on such an intimate relationship between venue and production team promises to yield some truly extraordinary engagement.

The cool weather is unwelcome after a week of being spoiled by clear skies and high temperatures, but my companion and I are grateful for a dry walk from the Underground. I’m familiar with the locale; my previous visits were for CoLab’s previous productions of Loot and Hunted which took advantage of the building’s surrounding neighborhood by staging half of each show outside the confines of the Factory walls before secreting guests down into the vaults and hidden passages of the interior. Tonight, our arrival is much more direct — a bearded gentleman in 1940’s military uniform awaits us at the door and immediately ushers us in.

We find ourselves serenaded by ’40s-era big band music as we duck into in a jerry-rigged bar festooned with Union Jack bunting. A jovial but tense staff in World War II garb tick our names off and invite us to have a drink as we’re briefed: we are back-bench Parliament members appointed as “designated survivors” in case of an attack on the sitting MPs. We’ve reported to our assigned garrison to wait out the blitz and our military escorts are so confident nothing bad will happen that we are encouraged to purchase shillings in the king’s currency to exchange for future libations in the bunker bar should the whim take us.

We’re then introduced to the space where we’re to spend the foreseeable future: an unfinished cellar with delineated areas for impromptu Parliament sessions, military tactics and deployment, propaganda composition, and empire-wide radio broadcasting. The walls are covered in relevant paraphernalia, the furniture is all in active use, and (as I note with unmitigated glee) every phone I pick up has a dial tone, which hints that they’ll be in use throughout the show. In spite of the meticulously detailed furnishings, there’s a small bitter part of me that remains skeptical (given my previous experience with participatory strategy-based shows) that the performance will be interactive enough to feel truly immersive. I am pleased to report that this misgiving was comprehensively wrong.

What follows is two hours of interactive joy. After a major attack decimates Parliament (no surprise) some members of the audience are elected by the populace into positions of higher responsibility (acting Prime Minister & deputy, minister of war, minister of public relations, etc.), while all others are defaulted to voting party members. Elected positions do not retain all of the power — every person present has the agency to affect the storyline as our majordomo-commanding officers deliver news from the outside world and lead us in calls to action. Tactical decisions made by individuals or the group are addressed in real-time behind the scenes by two resident historians, who respond with field reports of how the Axis powers react to each military strike and public statement. Broadcasts are drafted, military orders are issued, secret messages are passed, and hidden agendas are exposed. Tension and excitement run high until the bombs are overhead.

Get Shelley Snyder’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

SubscribeSubscribe

While the sound and lighting design are surprisingly dynamic given the intimacy of the performance space, the actors playing our military entourage deserve particular commendation. With every inquiry about another character’s motivations or what might happen if we made a particular military strike, our hosts provide a response fully motivated by their character’s knowledge of themselves and their comrades in that moment, reflective of how our specific narrative is developing. As they present each development and watch us debate (much as the real military reports to the legislature), they are wholly reactive to the results and not one leaves the playing space during the performance. I recognize at least one face from Loot (Peter Dewhurst, playing our lead host Douglas Remington-Hobbs), delighted that an old favorite is back to guide us through each crisis of our own making. During the climax, a large faction of our parliament flouts the main tactical objective and instead moves to unseat a particularly grating and incendiary elected minister who insulted other guests and made the experience less enjoyable. Our handlers adapt seamlessly to encourage this unforeseen development, while continuing to keep us narratively on-target.

In the throes of For King & Country, there is always something going on. There are specific plot events that fundamentally must occur throughout the performance, but the sandbox-style format provides multiple objective circuits affecting each other simultaneously. Guests are granted full autonomy to contribute according to their personal motivations and although teamwork is encouraged, there is the constant temptation to move against the pack to attempt to affect the storyline by individual means. There are engagement opportunities for extroverted and introverted guests alike, and the willing and lucky may have the opportunity for “easter egg”-style side-quests: as elected Prime Minister, I was presented individual opportunities to make military and diplomatic decisions independent of my constituency but at risk of impeachment. If I felt it was a choice I could not make without raising their ire, I would defer to the voting will of Parliament; but I did make some decisions (both clandestinely and publicly) that significantly affected the storyline. By the conclusion, the group discovered that several guests were operating under their own special instructions — I cannot provide more detail without revealing significant plot points, but it was evident that they had been offered alternate objectives early in the proceeding and decided to pursue them.

In terms of personal agency and engagement, Parabolic Theatre and CoLab have turned out a laudable performance in For King and Country that leaves me wishing for at least another hour in their painstakingly well-designed clubhouse, with a crowd eager to enact any combination of strategy, subterfuge, and sedition to bring about our ends. It is a must-see for the interactive theatre lover and with any luck the show will see an extension well into the fall.

Photos courtesy of director Owen Kingston.

For King and Country continues through June 10 at the CoLab Factory in London. Tickets are £29–35.

No Proscenium is a labor of love made possible by our generous Patreon backers: join them today!

In addition to the No Proscenium web site, our podcast, and our newsletters, you can find NoPro on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, in our Facebook community Everything Immersive, and on our Slack forum.

Discussion