Is it an accident that the work which had proven to be most effective emotionally in virtual reality has put the viewer alongside those who are most at risk in the world? Be it refuges awaiting supply drops, bombing victims in Syria, or witnesses to acts of brutality? When VR first returned to the public consciousness it was in large part due to the work of filmmakers like Nonny de la Peña, whose work debuted at America’s premier film festivals. There the movers and shakers of the film world were brought inside the magic circle of VR and shown the visceral power of virtual presence.

In the few short years since de la Peña’s Hunger in Los Angeles bowed at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival, VR has boomed and nearly busted as an industry. A steady march of artistic excellence being outpaced by Silicon Valley thirst for the next iPhone. The optimistic headlines of 2013 having given way to pessimistic reports on 2016 sales numbers.

No one, it seems, bothered to tell Oscar winning filmmaker Alejandro G. Iñárritu (Birdman, The Revenant) that VR is no longer supposed to be the Next Big Thing.

Thank God for that.

Iñárritu’s CARNE y ARENA (Virtually present, Physically invisible) made a splash at this year’s Cannes Film Festival and has now settled in for a year-long run at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. It is nothing short of the singularly most emotionally moving virtual reality experience I’ve yet to encounter. A stunning work that draws upon journalistic traditions, immersive installation art, and the technical wizardry of Industrial Light & Magic to create a piece of work that makes the implementation of VR at theme parks and multiplexes seem half-hearted.

Here VR is used as the primary tool in an extensive kit whose sum transcends its parts. All done in the service of telling the stories of Mexican and Central American migrants who risk death for the dream of making a new life in the United States. That this installation has arrived at a moment when the political life of the nation is grappling with the issues of immigration and growing racial resentment is apt. If anything it is something of a shame that a work on the scale of CARNE y ARENA wasn’t around and more readily accessible a few years ago.

Before getting into the heart of the material itself — which I believe is best viewed with minimal preparation — let’s close this off with both an acknowledgement and a recommendation.

For the former: there’s a reason I began this article by mentioning Nonny de la Peña. CARNE y ARENA is a spiritual continuation of her work, closest in theme to the seminal Use of Force, which recreated an infamous killing of a migrant at the San Diego border crossing at the hands of border patrol agents. The journey to this piece starts in her lab at the University of Southern California, in more ways than one.

The later is simple: go. Whether you’re a VR neophyte or someone who owns multiple head mounted displays, CARNE y ARENA pushes the envelope on VR as an art form — not just as a technical accomplishment.

SPOILERS AHEAD

The desert. In those moments just before dawn, before the rosy fingers inch out and chase the night away. Before eyes can adjust to the dimness there are voices. In Spanish. Outlines of figures moving just outside the edge of a clearing. Weary, their motions leaden, bodies spent from motion and weighed down with what belongings they can carry. That and something more, but before we know just what that is, the world erupts into cacophony.

Get Noah J Nelson’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

SubscribeSubscribe

CARNE y ARENA consists of two major elements: the installation and the VR short. The later is computer generated, as opposed to being a film shot in 360. This means that slightly stylized digital avatars stand in for the migrants whose stories are recreated, but it also allows for full freedom of movement within the space.

What elevates CARNE y ARENA above other VR experiences is the installation.

Before getting to the VR part, visitors are directed to a recreation of a border patrol detention room. Intentionally kept at a lower than comfortable temperature, this “cooler” is where you are instructed to take off your shoes and put on little booties made of panty hose material. Then you wait. Depending on when you arrived, you might be waiting for a while. The cold starting to get to you after initially being a relief from a warm day.

At a pre-arranged signal you’re summoned to go through the door, where a large room filled with sand, dramatic lighting, and two technicians. The sand partially swallows up your feet, and the unexpected presence of this element triggers the hyperaware state that comes with a really great immersive experience: the senses on edge, looking for the next surprise.

The techs wait, holding the VR rig, and are by your side during the whole of the experience, making sure that you don’t run into any walls through the application of a gentle tug on the backpack you’re given to wear.

The film itself lasts only a few minutes, but what lacks in length it makes up for in visceral punch. A frameless experience, the piece drops you into the moment before a group of migrants is caught by Border Patrol officers, who presence is heralded by a blast of wind from helicopter blades and flashing lights. The wind is real: delivered via the installation’s HVAC system.

The added elements of wind and sand compound the sense of presence already afforded by VR. This gives Iñárritu room to play with the VR toolbox turning limitations into strengths and working a more novelistic, impressionistic line. One of the most shocking twists of convention is what happens when you collide with one of the digital actors.

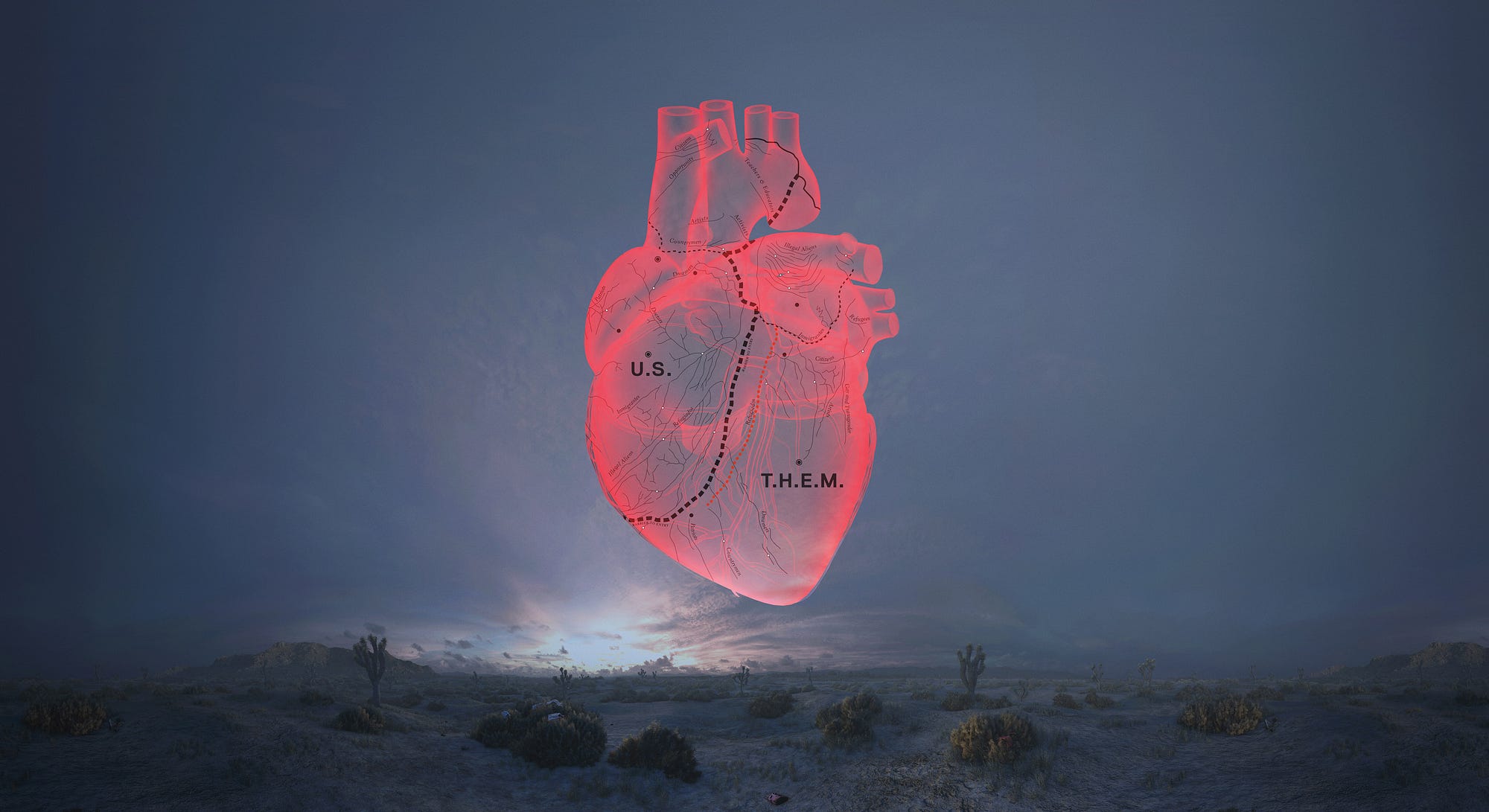

Most VR experiences would have you pass through like a ghost, instead CARNE y ARENA takes the opportunity to make the user’s ghost-like presence an asset. Instead of clipping through a virtual avatar we are plunged inside the bodies of the subjects. The sound of their hearts hammering in our ears and their internal organs pulsing with vibrancy.

My own accidental encounter with this caused me at first to reel backwards in shock. Then I pursued that moment over and over again: searching to see if there were a difference in how the migrant adults and children reacted. If the Border Patrol agents had steady heartbeats. If somehow the beating of their hearts could reveal a hidden truth that tied them all together.

This was not the only way that Iñárritu played with the convention of presence: at moments it was unclear if I was there alongside the migrants or existed outside their space and time. The sensation was uncanny as a Border Patrol agent’s eyes caught mine. Was he talking to me? Just what is my role in this world?

That blurring served the thematic aims of the work: to invite those of us lucky enough to spend our time and money in museums and film festivals to ask what our role is in relation to those who risk everything for the promise of a better life. Not the reality, mind you: just the promise.

VR as “empathy machine” has become a well-flogged cliche, one that has been deconstructed to the point of raw cynicism. Yet in the hands of creators of good intent the capacity of VR to create empathic connections suggest that it is less the default mode of the medium and more its ontological purpose. The illusion of presence that VR producers and engineers eagerly pursue finds its worth when put in service of this capacity.

The irony of our digitally connected world is that we’ve become more disconnected from each other as people even as information shrinks the mental distance between us. Instead of finding ourselves open to more points of view, the bifurcation of our selves into “online” and “offline” identities has created an ever widening political and cultural gap.

By pushing the limits on embodied presence filmmakers like de la Peña and Iñárritu use virtual reality to add back some of what has been lost to generations of media: the sense that the world — and the people in it — is wider, deeper, and stranger than the mind can hold in a single moment.

CARNE y ARENA (Virtually present, Physically invisible) is currently scheduled to play through June 2018 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Advance tickets are sold out through mid-September, but day-of tickets may be available in person on a first come, first served basis at the LACMA. Tickets start at $25 for members, and are a $30 add-on to regular admission for non-members.

Discussion