An interview with creator Dustin Freeman about the remote live experience

The Aluminum Cat is a new experience where a distributed set of participants play new recruits aboard a spaceship through their computer web browsers; however, all the characters aboard the ship are played by live actors in a studio. The remote experience brings together elements of improv, immersive theatre, gaming, and more.

We caught up with creator Dustin Freeman to learn more.

No Proscenium (NP): Can you tell us a little about yourself and your background in the immersive arts?

Dustin Freeman (DF): I build tech for immersive experiences. My PhD was on gestural interfaces for improv theatre performers (University of Toronto, 2015). I helped build one of the first realtime 3D scanning systems for the Kinect at Microsoft Research. I’ve worked as the in-house SDK and game developer for various XR platforms: Occipital, Moatboat, Fantasmo, Limbix. As CTO of Raktor, I built one of the first live Mixed Reality streaming shows with audience participation.

I’m now the Founder and CEO of Escape Character, building a platform to connect live performers and audience members for telepresence experiences.

NP: What, in a nutshell, is this project about?

DF: In our show, you and your fellow new recruits to The Interplanetary Forces can only communicate through mouse gestures and emotes, while our actor plays every character you encounter aboard ship. Very quickly, you discover that not all is what it seems, and there’s a possible ongoing mutiny. You need to be careful who you talk to and how. The show becomes increasingly open-ended as you get more into it.

If I was to describe it in genre terms, it’s a campy space action comedy — almost Coen Brothers-like, as you and the characters you meet try to wrest control of the situation, with mixed results. Audience member have said they felt “a weird kind of camaraderie” communicating with their other, totally anonymous, audience members.

NP: Why did you create this experience? What inspired you?

DF: Almost all immersive experiences with live actors can only be experienced in person. For accessibility for both performers and audience, I’ve been exploring what a remote show looks like in various formats since 2016. There’s some non-obvious surprises, for example text and audio chat doesn’t work very well if you have more than a couple audience members, and want to keep the show moving forward smoothly.

The Aluminum Cat is the first format I’ve felt that really works — that doesn’t just feel like TV, but feels like indie immersive theatre in the sense of sharing presence with the actor and other audience members.

NP: Why choose to work with improv actors playing each character live, rather than doing something pre-recorded or canned?

DF: Even if a show is interactive, there’s a spectrum of agency from pre-canned content (Choose Your Own Adventure, Netflix’s Bandersnatch), and completely open longform improv Harold, in the style of Del Close and Charna Halpern. I’m a very experienced longform performer, out of the Toronto improv scene and the Canadian Improv Games. That style of improv is typically done on a barebones, black box stage, with no extra input that would constrain how the totally spontaneous show could unfold.

The magic of interacting improvisationally with an audience is that you get very practiced at steering the audience towards a certain feeling without it being forced, and responding to them in an authentic way, and letting that response persist throughout the show. The audience interaction moments in The Aluminum Cat are not just fill-in-the-blanks mad-libs; actions our audience take very early in the show will affect how every character responds to them throughout.

Improvisors often talk about “the game of the scene,” where you discover what a character’s shtick is — once this is established, you can heighten and explore it in other settings. The big script for our show is an 11 page “world bible,” which includes all characters and the games they play. During the show, the performer has a one-page-per-act checklist of information that needs to be delivered at certain times. This acts as a minimal scaffolding supporting the logistical parts of the story, and within that the improvisor-audience response is very freeform.

NP: What kind of software does the experience run on? How are you getting the actors into the remote experience?

DF: If a live experience runs from a downloadable game, there’s a chance that if someone else you’re seeing the show with is running late (I’m sure we can all relate), then they won’t have read the download and install instructions. We wanted to make “getting to the show” as easily as possible, so it runs entirely in the browser, using our custom video streaming and filtering solution. I wrote a little server backend for handling other audience/performer metadata that’s reasonably low latency and scales nicely. The server is written in Rust, which is my new favourite after lots of professional software engineering in C, C# and Python. Fortunately, now that we’ve done this, we can reuse it for anyone else’s show!

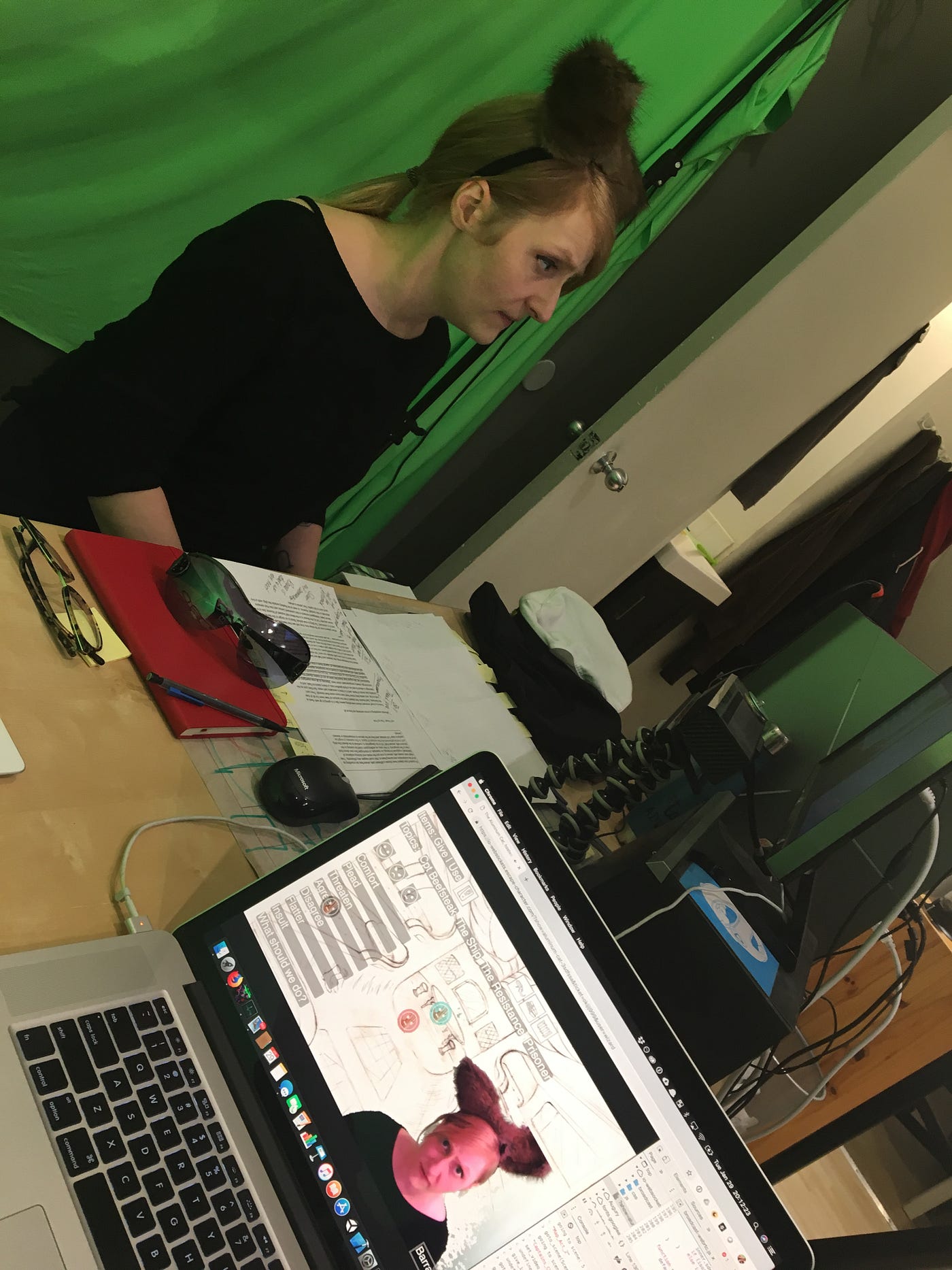

The actor runs shows from Escape Character’s green screen studio in Toronto, surrounded by the costumes they used for each character. In the future, we’ll switch to Snapchat-style augmented reality costuming, so it’s easy to run the show from anywhere, without a green screen.

PS. Come talk to us if you want to run an online show.

NP: How is the audience incorporated into the work? What kinds of choices can the participants make?

DF: There’s not really pre-canned “X or Y” choices, and no polling the audience for what to do at given times. I think when people aim for “interactive” theatre, they try to give lots of chances for the audience to explicitly affect the show as much as possible. I’ve done a lot of shows this way and…

I am of the opinion that doing this removes too much stakes and makes the audience the master of the world instead of a collaborator. I prefer the word “participatory,” where the audience is involved, and then discovers their agency through encouraged play.

My favorite participation moment in our show is when the audience cleans the Latrines — it’s very slapstick and a good physicalization tutorial, but when you think back later given what you know about certain characters at the end of the show, pretty morbid. Towards the show, you get access to more and more items that give you greater agency. At the start of the show, some audience take a ton of independent initiative, and some don’t. Our early tutorial scenes are designed to get to know the audience, and teach them when to take initiative and when they’re being too aggressive, and then the real show starts.

NP: How are you designing around audience agency, consent, and safety?

DF: It’s funny how I feel it’s so much easier to respond to this question given that our audience is remote. I’m like, “Of course it’s safe, you’re never in the same room with the actor or the audience, and don’t share your voice, camera, or your identity.” Our show doesn’t explore particularly unsafe topics, except for a campy space rebellion with some light off-screen murder. The audience can close the tab at any time, and we don’t have extended 1-on-1s.

Unlike an in-person show, when the show ends after the curtain call, in our show you’re immediately no longer in the same digital space as the people you saw the show with. We’ve had a couple people complain that this felt abrupt, even though our show has a clear narrative conclusion. Some have suggested we all send them to an optional shared chat room.

Even if this show doesn’t explore particularly unsafe moments or topics, it’s interesting that because this show involved a high degree of audience agency and connection, losing that connection to these anonymous people you’ve built a bond with can feel sudden.

There’s a need for shared commiseration as a form of aftercare, so we’re going to work on making this chatroom — a sort of digital theatre lobby.

NP: What’s the audience response been like so far?

DF: I’ve loved the tweets and little anecdotes! My most favorite story is that we had a group that used to play escape rooms in the same city, but now some of them live on different continents. This is the first immersive-like activity they’ve been able to do together since. I’ve had someone call it “delightfully weird” which I consider an excellent compliment. Our small audience groups can only identify each other by color, and I’ve had people tell me they enjoy making little gestural callbacks, and trying to build a model of each other’s personality based on what little they know.

We’ve had some of our audience say “the scripted lines are funny,” but honestly, there’s only about 8 scripted lines in the entire show, all near the beginning. Stephanie Malek, our original cast who helped design all the characters is just really funny, and makes each show a bit different by responding authentically to the audience. Our writer, Natalie Zina Walschots, has a LARP background, and has written a scenario with just the right amount of information so you can play in it, without feeling too constrained. I hired our background artist, Suzanna Komza, based on her portfolio initially because I thought we were going to do a fairy tale setting. When Natalie chose a scifi setting, I got nervous that Suzanna wouldn’t want to do it, but she got quite excited and we ended up with an aesthetic that’s somewhere between H.R. Giger and Barbarella. We had one audience member call it “highly vaginal.”

NP: Who is the ideal audience member for this show?

DF: First: have you always wanted to attend an immersive show, but limited by geography or mobility? Then this is made for you.

Second: if you are intimidated by actor interaction or being in a space with others, then this is also great. The power of mask, where you get to be someone else, and fairly anonymous, is strong here.

Otherwise, if you like goofy space adventures where you and your fellow idiots get up to trouble, running into a cast of increasingly weird characters, then you’ll have a great time.

NP: What do you hope participants take away from the experience?

DF: Primarily, I hope that they come away feeling like they went on an adventure that was personally theirs — I’ve been present, in-person or remotely, for every single show since late January and it’s still surprising how differently each of them unfold.

Academically, I hope they come away thinking about how expressive the ultra-minimalist communication channel was in this show. The conversational UI used to be way more complicated, but we kept cutting more and more as we realized how expressive the audience could be with less. I hope this challenges other shows to think outside the box in audience communication, whether in-person or remote.

The Aluminum Cat continues, online. Tickets are $10–20.

NoPro is a labor of love made possible by our generous Patreon backers: join them today!

In addition to the No Proscenium web site, our podcast, and our newsletters, you can find NoPro on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, in the Facebook community Everything Immersive, and on our Slack forum.

Office facilities provided by Thymele Arts, in Los Angeles, CA.

Discussion