In most mediums of modern entertainment, sound is the one design element that easily projects beyond the fourth wall — be that a stage or screen — and immerses the audience.

Whether that is through the use of the rear channels in a 5.1 audio cinematic setup, or the strategic use of speakers placed throughout a theatre, sound can pull our focus or swirl around us. But in our modern life, thanks to the ubiquitous ear buds, we are now so used to audio even closer than that: sound that lives entirely in our heads. Which allows us to block the rest of the world out. To what end does this mediate our engagement with environment and society as a whole? Over the past twenty or so years, there have been various experiments on headphone (or headphone like) theatre which have probed this question. Each piece takes a different approach, but they all tend to force us to filter our viewpoints to see what is often hiding in plain sight.

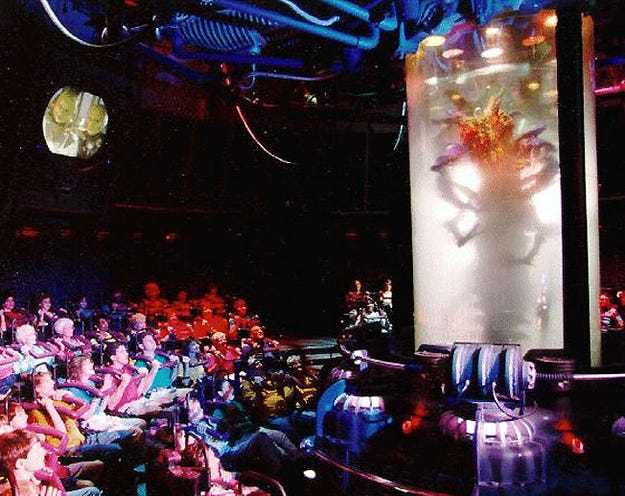

Before we even get to the ubiquitous headphones, we should understand the power of binaural audio. Binaural audio techniques replicate our natural sense of hearing by placing two microphones where a human’s ears would be and having a foam dummy head in between. Not using headphones, one of the best examples of how well binaural audio could work in an immersive entertainment experience would be the single scariest attraction that Disney Imagineer’s ever built: The ExtraTERRORestrial Alien Encounter.

This attraction plunged the audience into darkness while having soundscapes of an alien walking around a theatre. This was done to great affect by placing speakers very close to the guests’ ears to create a binaural soundscape so when the “monster” would “walk” behind you your brain would be tricked into thinking that it was inches from your neck, breathing on it. Frankly, I prefer this approach to audio presentations as it can help create a more collective experience while maintaining the close proximity needed to create a three dimensional aural environment. But that’s besides the point, if you were to look at most videos of the attraction, there are several minutes where nothing is seen at all, and you then get a sense of how powerful sound can be in creating terror in an audience.

Get Martin Gimenez’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

SubscribeSubscribe

It’s also interesting to note that Alien Encounter was made before ear buds became entirely commonplace, so at the time, we weren’t nearly as able to walk around with high quality audio in our pockets. Despite the strengths of binaural audio for headphone theatre, technical requirements on both the content creation and the delivery systems would keep this tool away for awhile.

Flash forward ten years…

Once the iPod became a fixture in everybody’s pocket, the expectations of the audience, and the ability of tech savvy theatre makers shifted greatly. Now, in addition to commenting on whatever location is being investigated, the mere act of listening and participating in a public space is being investigated. Marike Splint’s piece Among Us does this masterfully, by instructing it’s viewers to engage with each other and the public at large in the middle of a crowded train station at rush hour as well as a public park. The other, “simpler” version of headphone pieces tend to feel more like radio plays (with expansive soundscapes and musical scoring) meant to be seen in a “specific” location^, David Leddy’s piece Susurrus, which played the Without Walls Festival in San Diego, is an excellent example of this.

It was only a matter of time before somebody would combine the intimacy of a radio play with the flexibility of binaural recording. That it is done in real time, in front of an audience, every night as part of The Encounter by Simon McBurney/Complicite elevates this to the pinnacle of headphone theatre in our current moment. By intentionally pulling the curtain back on the techniques and tools he will use to make the audio landscape work during the first fifteen minutes of the show, we are more thoroughly brought in to the compelling story of a photographer encountering an as yet “un-discovered” tribe*. Unlike the site specific theatre which calls for a more simple approach to the audio product, the fact that the audience is entirely stationary, allows for the aural landscape to appear to move rather dynamically. Much like motion simulators, but without the nauseating side effects!

Listening to anything on headphones allows for a completely different world to be created in your head. As the technology continues to develop (don’t get me started on all of the new changes in the VR world, and how ambisonics are changing how we capture audio and hear it), I hope that these various experiments are only a preview of what’s to come.

^This is what one colleague once demarcated as the difference between “Site Specific” theatre and “Site Sympathetic” theatre, where a “Site Sympathetic” production can be dropped in similar locations to where the original piece was created, whereas a “Site Specific” can only work in one location.

*There is an excellent tradition of highly technical devised theatre in the UK, another favorite practitioner, who tends to deal more with making a film in front of an audience’s eyes is Katie Mitchell, seriously, look up her piece Waves.

Discussion