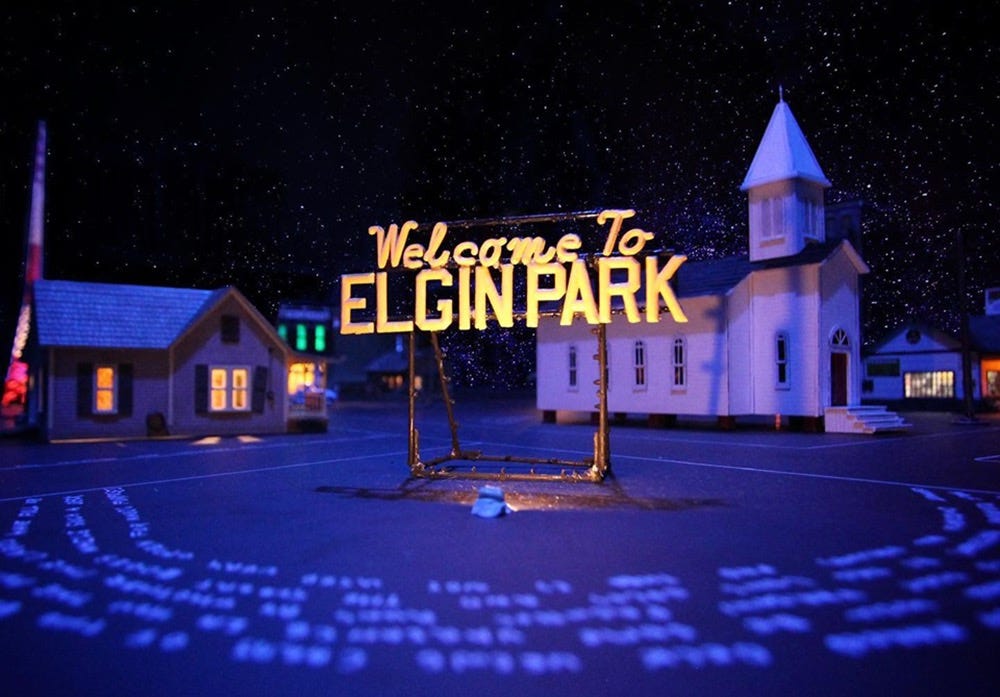

Wildrence, the venue where Elgin Park is performed, lies behind an unmarked blue door on Canal Street. Outside the door is the hustle and bustle of Chinatown: the mingled smell of food and trash, the cacophony of honking cabs, and the press of crowds. But when I ring the buzzer to get in, I am whisked into an entirely different reality. Chinatown ceases to exist. I am in Elgin Park.

I am greeted by a smiling man, Drew Petersen, in a rumpled suit jacket. He is barefoot, and beckons me to follow him down the stairs, into his home. I linger, taking a moment to examine the framed photographs on the wall. By the door, a precarious-looking stack of books sits with three empty milk bottles on top. I pick one up; it is labeled “Paul’s dreams.” There is a translucent slip of paper inside that I want so badly to read, but I see that my host is waiting for me at the bottom of the stairs, and I reluctantly put it down and hurry onwards. I am the last guest to arrive. There are approximately ten others milling around a dark foyer, examining photographs, books, postcards, and the flotsam and jetsam of crafting, including an assortment of painted miniature models of everyday things like benches, bushes, and retro-looking cars.

Our guest’s home is warm and smells welcoming, like a candle has been burning for hours and has just recently been blown out. It is not a big house, which the man apologizes for in the fussy way that all hosts do. An old rotary telephone sits, ominously, on a stand under a bright spotlight — the only thing illuminated in the otherwise dark room. The man stands by the phone and smiles at us, not speaking, until we quietly arrange ourselves in a circle and watch him. The phone begins to ring, and our host answers it, hesitating. We listen to a recorded message which our host seems to have heard many times before, mouthing the words alongside the recording. The message is a conversation between a man named Michael Smith and a detective. Michael’s brother Paul has gone missing.

Our host, whose identity is still unclear to me, asks us to follow him into another room. We shuffle out of the foyer and through a door into the living room. Petersen disappears and we are alone with another actor, Christopher Stevenson, also barefoot and wearing an equally wrinkled suit jacket. This door, much like the door to Wildrence itself, appears to have been another portal. We have been transported back in time yet again. Big band jazz music crackles out of antique gramophone in the corner and we sit around the living room table on mismatched couches and kitchen chairs. The actor begins to set the stage; Michael and Paul are children and their parents are having a party for several friends who we, the audience, ostensibly play. Michael is a shy child, but his brother Paul is an exhibitionist who declares his intention to perform a magic trick, where he will climb into a wardrobe and disappear.

And disappear he does — he first disappearing act in what becomes a successful career as a world-famous magician. While Paul’s star ascends, however, Michael grows reclusive, taking over the Smith family home and interacting with Elgin Park through the figurines he makes of it rather than with the real town and its people. It takes the catastrophe of Paul’s mysterious disappearance to force Michael to confront reality, which is when the story really begins.

Our hosts tell us the Smith brothers’ story. It becomes apparent to me that the performers in Elgin Park are narrators rather than characters in the world. Though the show is linear, it dips out of time and space, jumping forward by weeks in some places, going forward years in other scenes, with little to no explanation of the passage of time. My initial sense of being a guest in Elgin Park is completely gone; I feel more like a ghost. We float above the action, unseen and unheard by anyone in the town, with only the narrators to guide us. We hear Michael’s story but are not a part of it, unable to interact with anyone or impact the chain of events. This distance proves to be both physical and emotional. We never actually see Michael or anyone else in the story, just hear the tale from Stevenson and Petersen. Like hearing a story about a friend of a friend, Michael’s story is interesting, sure, but I found it difficult to empathize fully from so far away. While we lose out on understanding Michael up close from this bird’s eye view, Elgin Park makes up for it by allowing us to see the town in a way that we never could if we focused solely on Michael. Elgin Park becomes a character unto itself. We see its beauty and charm, but also its dark, hidden corners and unsavory characteristics. This lends itself to a mingled sense of claustrophobia and charm, and allows us to understand how Michael can simultaneously love his town and be afraid of it.

The tension of these two competing forces is where Elgin Park shines. The show uses Michael and Paul’s story as a vehicle, and the town of Elgin Park is its destination. The storytelling transports us, aided by inventive sound and lighting design which add emotional depth to the story. But it is the Wildrence space that fully immerses us in the world of Elgin Park. Every detail feels true to the sense of rural, vintage, Americana that defines Michael’s town and his life within it. The sounds — the swing music playing in the kitchen, the scream and pop of fireworks exploding over the town during a Fourth of July celebration, the occasional snippets of staticky, Transatlantic-accented radio programs fading in and out of earshot — give us a sense of time and place. Even as someone who has seen the Wildrence space used in a variety of different shows, Elgin Park is able to make me feel that the set kitchen we’re in is not a set kitchen at all, but in fact Ms. Smith’s kitchen, where Michael and Paul have entered before us. The smells — the deep, autumnal scent of cloves and cinnamon, and the wafting smoke of a candle freshly blown out — are what ties it all together for me. By engaging the senses, we are effectively transported.

Still, I wanted more from the story, and a deep sense of place — however strong — didn’t feel complete enough to fully satisfy. The atmosphere is there; it is haunting, magical, melancholy, and sweet. But the story’s failure to connect emotionally leaves me feeling let down when the mystery is finally solved and the proverbial curtain falls. By making Michael a secondary character in his own story, the emotional reveal at the end feels less “Wow!” and more “So what?” Rarely do I see an immersive show that so perfectly captures a feeling, a time, and a place the way Elgin Park did. If we could have seen Michael in the same way we saw his town, the combined effect would have been dazzling. But even without the central character having a stronger presence, Elgin Park’s ability to fully immerse the audience into the environment of the story makes the show worth seeing.

NoPro is a labor of love made possible by our generous Patreon backers. Join them today!

In addition to the No Proscenium web site, our podcast, and our newsletters, you can find NoPro on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, in the Facebook community Everything Immersive, and on our Slack forum.

Office facilities provided by Thymele Arts, in Los Angeles, CA.

Discussion