Quaranteam reminds me of Westworld. No, the latest experiential production from ABC Interactive doesn’t include robots disguised as human playthings housed within a psychological experiment fronting as a theme park. However, Quaranteam does illuminate pivotal themes of Westworld’s first season. Let me explain.

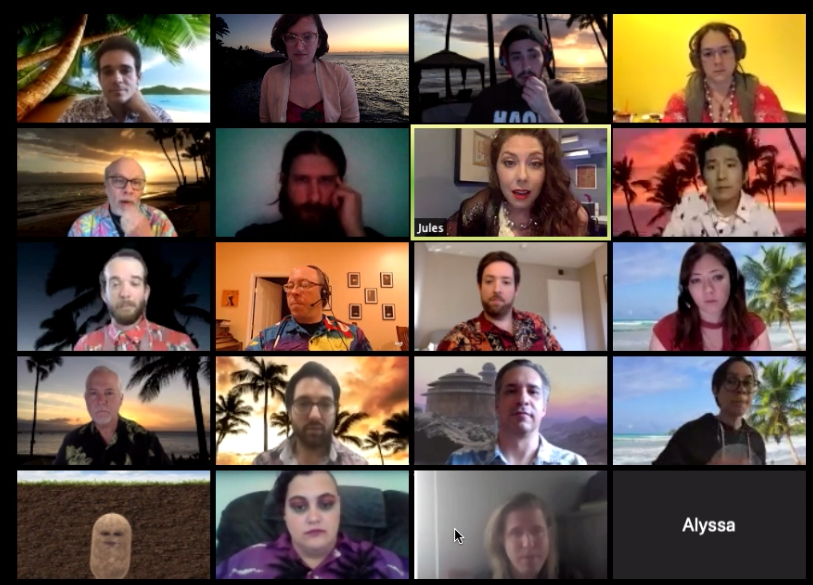

Quaranteam is a six-week experience set inside “RFIDirect,” a fictitious radio-frequency identification (RFID) technology company based in Denver, with all its team members, including the “new hire” participants, working from home as they navigate challenges brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. There are three ticketing tiers, ranging from observation-only up to full inclusion as a team member. For two weeks I jumped in as the latter, assigned to RFIDirect’s social media and PR team. This level offered access to the company Slack workspace, both public and private channels, and the opportunity to join a weekly combo of team meeting and happy hour via Zoom.

Prior to RFIDirect’s Slack launch, I received a video link from Sue Hall (played by Annie Lesser), the head of HR. Rather than a welcome greeting for new hires, the video was the camera and audio check between Sue and Benjamin “BJ” Perez (Jason Rosario), the IT and security specialist. Sunny and lovable, Sue weebled through the brief test run with encouragement from BJ. The video was charming, but absent any instruction, key details, or real mystery.

That evening, before joining the new Slack workspace, I considered: who do I want to “be” in Quaranteam? The show’s code of conduct rightfully prohibited inappropriate or unsafe behavior such as hate speech or sexual harassment. Participants were also barred from breaking the reality of the show. But in the midst of a few other disclaimers and guidelines, there were no advisories about personas or storylines. To me, enrolling in the game meant joining with a like-minded spirit, which included adopting a character of sorts. At this point I had no details about the other participants and only minimal information regarding the company and cast. I decided on “Lorraine Teitelbaum”: effusive, relentlessly positive, and overwhelming in her use of emojis.

I spent about an hour in RFIDirect’s Slack on launch night, feeling increasingly confused. As a kickoff party platform, utilizing Slack was like trying to breathe through a wet paper towel: inefficient, uncomfortable, and even stagnant. I settled on a reasonable message pace, leaving space for the cast to drive this inaugural, remote get together. Instead, we stumbled along, cast members and participants joining, commenting, and signing off, our interactions still missing any exciting discoveries or dramatic tension.

Over the next week, numerous Slack messages were posted. There was the “arrfid” channel, initially reserved for adorable canines and then quickly expanded to any cute critter. Naturally, quokkas made an appearance. There were other public channels: “general,” “random,” and “important announcements.” I was added to the private channel for the PR and social media team, helmed by Jules Jennings (Dasha Kittredge), a beautiful maven with just the right emotional prescription for social media.

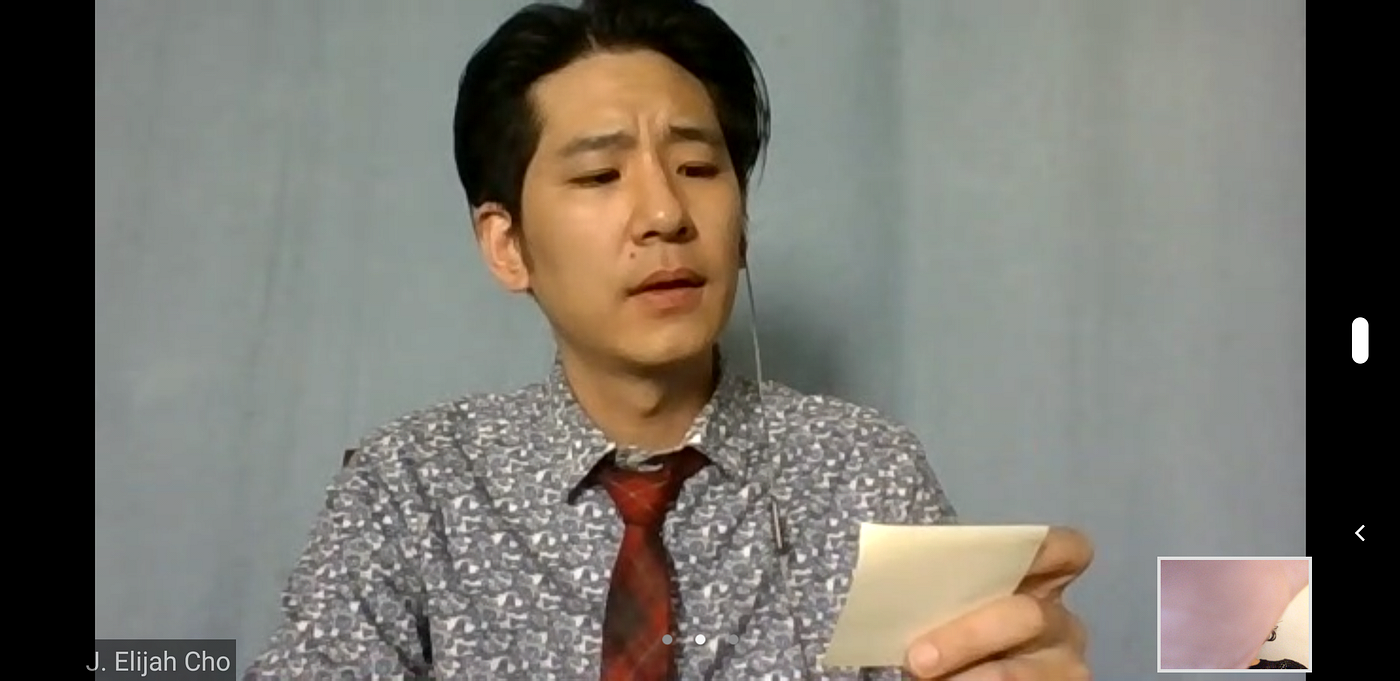

In the midst of this Slacknado, another video message arrived, this time from CEO Duncan Donner (J. Elijah Cho), entitled “State of Our Company.” Duncan awkwardly lurched through some jokes while providing more backstory for RFIDirect. He forecasted the company’s impending bankruptcy, unless the team united to develop new products and revenue streams. Concurrently, Jules Jennings prodded the social media team on Slack: How could RFIDirect pivot in its offerings in order to remain relevant? What proposals could we present to the rest of the company in the upcoming Zoom meeting?

And this is where I started to think of Westworld. The first season was a brilliant cascade of exploitative desires and existential repetition, of character drive and trajectory. The framework of the park created a baseline of reality and suspended upon this scaffolding was a hyperrealistic world of fantasy. We watched people — the guests — revert to contracted emotional spectrums, while we watched the robots — the hosts — strain against their coded predestination. What worked so well about that first season was the audience’s dual fantasy: living vicariously through human debauchery while exploring the emotional depths of personal purpose. Neither of these carried serious risks for the viewer; we rode that roller coaster, a train balanced on its carnal and philosophical ends. And that ride actually took us on thrilling hammerhead turns and speed hills. Even if we ultimately tracked back to the station, we returned adrenalized and maybe even changed in some small way.

Get Laura Hess’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

SubscribeSubscribe

With Quaranteam, I inclined up the lift and then… came back to the station. I didn’t go anywhere because there was no fantasy. Quaranteam was birthed underdeveloped and too close to reality. The influx of Slack messages quickly felt obligatory and tedious to sift through, although I appreciated the prolific wittiness of “Brian T,” a fellow participant in the social media team. I have only a cursory understanding of RFID technology. I am not a social media or PR expert. These would not have been problematic, except I was unclear as to how far I could stretch the absurdities of the game, because, outside of the code of conduct, the parameters weren’t well defined.

Quaranteam bills itself as “a chance to laugh at ourselves during these trying times,” and “part sitcom, part job you don’t want to get fired from, and all from your home.” The stakes, however, aren’t there. Already, we are all in our homes, all of the time, save for the demands on essential workers. In order to be averse to getting fired, I first need to care about my “job.” It’s challenging to drum up investment and emotional attachment when: I had to cobble together a basic persona, based off of a thin membrane of show tone and characters; the core hurdle is the same horrifying core hurdle the entire world is currently facing; and this experience isn’t adding any real fantasy, surprise, or delight to my daily life.

Which circles us back to Westworld (spoiler alert). Toward the end of the season, Bernard Lowe, the park’s programming director, learns he is a non-human host. Later, he and Robert Ford, the park’s cofounder, discuss consciousness and the threshold for sentience. Ford elucidates, “Every host needs a backstory, Bernard, you know that. The self is a kind of fiction for hosts and humans alike. It’s a story we tell ourselves and every story needs a beginning. Humans fancy that there’s something special about the way we perceive the world and yet we live in loops, as tight and as closed as the hosts do, seldom questioning our choices, content for the most part to be told what to do next.”

Unlike Westworld’s hosts, Quaranteam lacked a robust and compelling backstory. I imagined this game would be akin to a remote, professional version of Clue: I would be engaging with outlandish characters within a hyperrealistic world of comedic mystery as we sought to save the company. Or maybe it would be reminiscent of The Office by providing a safe space to play out nonsensical fantasies of what we wish we could say or do in a work setting. I might even be assigned a persona, with a critical task or costly misconception, interwoven into an overarching storyline.

Instead, my pretend colleagues adhered to a more realistic barometer, with stale, rigid loops. Participants and cast members proposed solutions such as generating new revenue streams with biodegradable PVC or paper-based RFID products and introducing RFID options for pedestrian street crossings at traffic lights, to reduce COVID-19 infection from community transmission sites. There was also a hacking scandal due to Jules Jennings’ lax security protocol; important R&D details were stolen and leaked, along with company passwords and key data.

I tried pushing back without overstepping. Lorraine Teitelbaum sent a Slack message stippled with emojis, proposing an all-out animal-centric meme offensive, heavy on squirrels and Corgis, to counteract the PR fallout as a result. The response was measured positivity. I wanted something unusual to happen. I wanted an escape from the incredible mental load we are collectively carrying. I didn’t want a work-lite replica experience. And since my departure as a team member, I remained in the show as an observer. HR manager Sue’s wife tested positive for COVID-19; two employees revealed they’re in a romantic relationship; the cast started a baking challenge with their sourdough starters. In short, very little has changed regarding the show’s pain points.

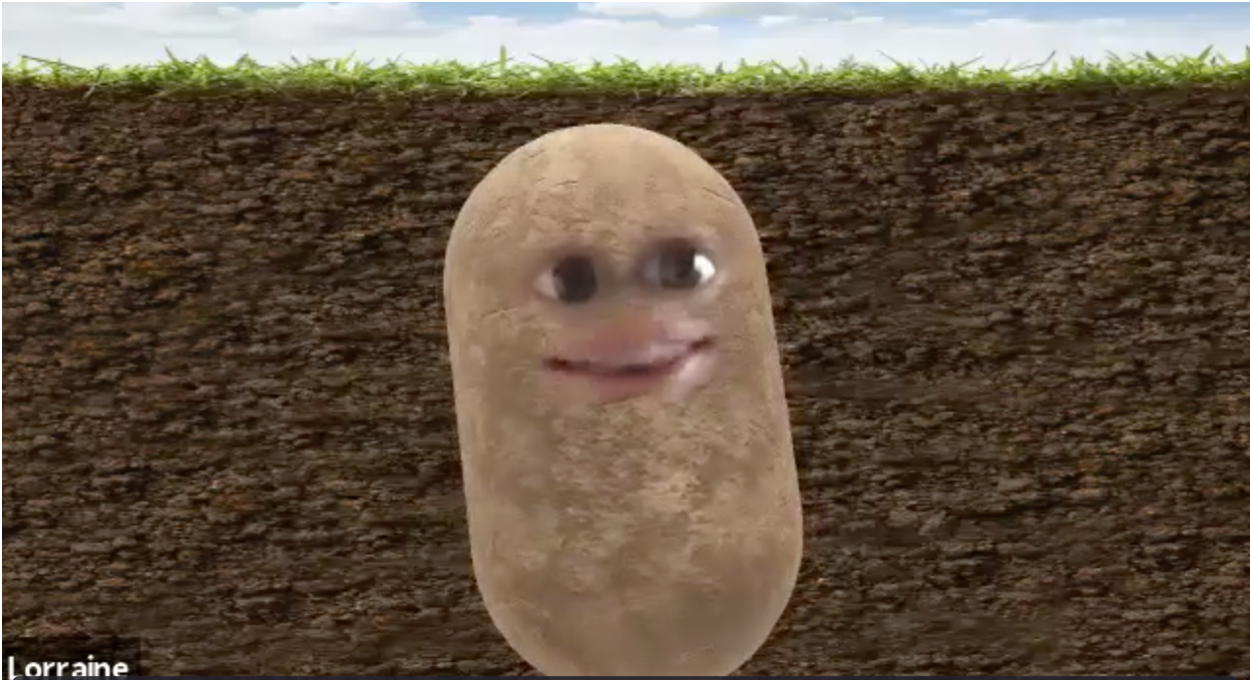

The one attachment I developed during Quaranteam was to a potato. For the first team meeting and happy hour, I imagined Lorraine as the type of person who would get stuck in a potato Snap filter, just like Lizet Ocampo, the political director of People for the American Way, who accidentally conducted an entire video meeting as a potato. For Quaranteam, being a potato heightened the reality of the world into a place of ridiculousness, a joyful reprieve; it felt like play. As a potato, I felt liberated from myself and reveled in my carbohydrate-d nature.

In Westworld, in another conversation with Bernard, Ford tells him, “When we started, the hosts’ emotions were primary colors: love, hate. I wanted all the shades in between. Human engineers were not up to the task, so I built you. And together, you and I captured that elusive thing: heart.” Quaranteam may have thought that a parallel universe, professional-setting experience would be an entertaining salve to our global crisis and existential teeth gnashing. But it failed to deliver a full-spectrum world of buoyant escape, which is indeed a tall order. The idea ultimately lacked heart and was served up half-baked. Having been a potato, I feel qualified to say that.

Quaranteam continues through May 15.

NoPro is a labor of love made possible by our generous Patreon backers. Join them today!

In addition to the No Proscenium web site, our podcast, and our newsletters, you can find NoPro on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, in the Facebook community Everything Immersive, and on our Slack forum.

Office facilities provided by Thymele Arts, in Los Angeles, CA.

Discussion