Seeing You joins a growing number of pieces developed before November 2016 that seem to be a direct response to the election of Donald Trump. That’s because Trump’s America existed long before Trump was elected. But you know that. Seeing You knows it too, and proves how deep its knowledge goes with a trip into World War II America that roils around you like some kind of phantasmagoric The Crucible.

Randy Weiner and Ryan Heffington put the show together. Heffington is an edgy, experimental choreographer who’s worked with the likes of Sia, Arcade Fire, and Florence Welch. Weiner produced the NYC production of Sleep No More and was the driving force behind Queen of the Night and The Donkey Show. They’ve done pop art and they’ve done sex-filled dinner theater for impressing your business partners — and now it feels like they’re pissed off and ready to make a point.

Seeing You plays in a huge open space, bisected and trisected and multi-sected by sliding curtains, moving stages, modular risers, and more intimate areas created with lights or the bodies of audience members or both. Ten years ago this use of space might have been dazzling for a New York audience, but now it felt restrained, even a bit to be expected — and of course it does. We’re out of the innovation stage of immersive theater where everything is filled with the shock of the new. We’re in the going deep stage.

The scenes in the first thirty minutes or so of Seeing You take place all around you. They’re little vignettes of life in small town America, pulsing in and out like an extended trailer for a homefront movie about World War II, the kind of movie that sees the pain of a sweetheart going off to war as a greater tragedy than the war itself, the kind of movie that equates bravery with nationalism, the kind of movie that seems to be critical of violence and loss of life, but celebrates war as a force that gives life meaning. In other words, almost all WWII movies.

But then it turns.

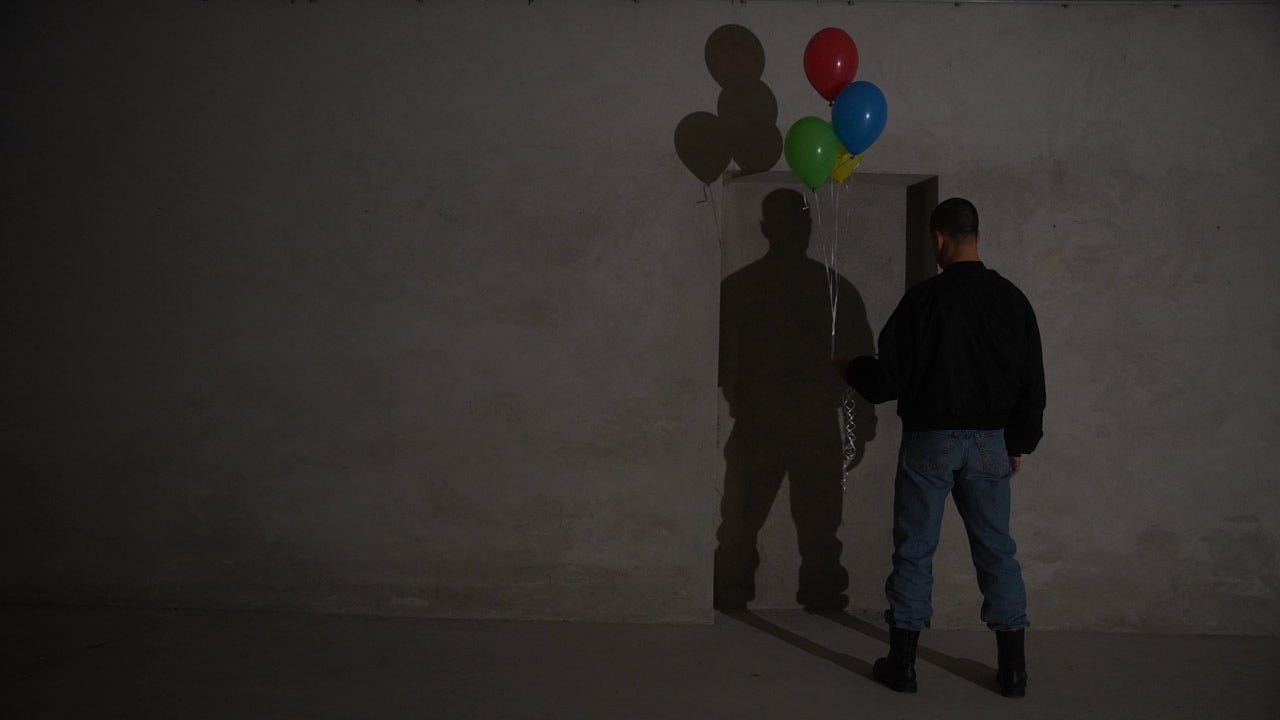

Seeing You weaponizes nostalgia, taking aim at the notion that there are no good wars except for “the American Revolution, World War II, and The Star Wars Trilogy.” Seeing You seems aware that there is something darkly erotic in that urge for righteous violence, and that urge that can take hold of any country that has succeeded in creating an enemy — foreign or domestic.

This sort of nationalism is an engine for racism, and Seeing You doesn’t make it seem as if everyone in WWII was a wide-eyed G.I. out to protect every single person is his hometown. Those wide-eyed G.I.s are trained to see with the dark eroticism of righteous nationalism, and that feeds into the racist gaze. These points are made in tiny, intimate moments, as well as broadly erotic ones. It’s uncomfortable. It’s relentless. And then, all of a sudden, it’s funny.

At one point in the piece there’s a hyperreal U.S.O. show that brings all of this together: the dark eroticism of aggression, the racist gaze, threat of the militarized man, the profound terror of the atomic bomb. It’s broad and showy, so if you only like your art subtle and oblique, this isn’t the piece for you. But if you like your politics fed through sexy dancers and garish costumes and thumping music and cross-dressed G.I.s doing stage dives, then step right up.

But of course it’s all fun and games until you actually get to the war. When war itself is finally depicted, it is not a noble struggle, or a fair struggle, or a time when boys become men, or a time when our country triumphs over evil, it is a traumatic grotesqeurie where giants — literally giants — destroy the human body. “There is no war, there is only the dalang,” but by sidestepping the realism Seeing You seems to continue to make its point: war isn’t fair, or nice, or balanced, or sensible, and its depiction shouldn’t be either. If the depiction of an atomic bomb doesn’t drive you slightly insane, that depiction has failed, and Seeing You does its level best to depict the cosmic horror of The Bomb.

There is a downside to the modular structure of Seeing You. The evening feels less like a progression than it does a kind of static statement. Images and scenes get more intense without developing layers. Each episode has its own complexities, but those complexities don’t seem to build on each other. The same issues are represented over and over again, with more color and higher volume, which can get tiring.

That all may be the point, though. Because the final moments of the piece demonstrate that Weiner and Heffington can pull connective structural tricks when it suits their purpose. A twist reframes the entire evening in a moment that forces reflection on everything that went before, doubling down on the theme of using nostalgia to explore nationalism.

Despite its period setting, Seeing You feels relentlessly contemporary. It is an immersive The Crucible that evokes Trump’s America with greater force than any of the plays written post-election. Contemporaneous pieces can’t tell us more about what it feels like to live in Trump’s America better than our bodies can on a moment to moment basis, so Seeing You does something entirely different: it explores the historical links between nostalgia, nationalism, and war with a complicated mix of anger, exuberance, eroticism, and deft choreographic moments.

Discussion