Broken Ghost Immersives — the brain child of Austin Anderson and Ian McNeely — first hit our consciousnesses last year with their interactive, RPG-inspired experience, The Bunker. Writer Leah Ableson called it “a tribute to the imagination” and a “celebration” of audience agency in immersive. Next after that, they got our attention with the super-villain convention Rogues Gallery, which writer Edward Mylechreest called a “glorious evening of scum and villainy.” They’ve since re-imagined the piece and are staging both Rogues Gallery (version 2) and The Bunker at the Wildrence space in Chinatown, Manhattan later this summer.

In advance of both shows, we hit up Austin and Ian with our Immersive 5 to learn more about their approach to creating interactive and immersive experiences.

No Proscenium (NP): What does “immersive” mean to you?

Austen Anderson (AA): A theatrical form of storytelling where the audience plays an active role in the formation of the story and/or shape of the experience.

Ian McNeely (IM): A greater level of engagement and depth of experience.

NP: Why (or why don’t) you think of your work as immersive?

AA: Our work is immersive because we focus our experiences around the question:

“What meaningful agency does an audience member have in this piece?”

For us, the answer to that question can take a lot of different forms. Sometimes it looks like a play with branching paths, or performance art where audience members can enter into the piece and become a part of the story. Other times it’s a more board game-like experience where player choice drives the entire shape of the narrative.

But as long as the piece has something in it that’s reactive, something that can’t exist without audience interaction, then I would consider it immersive, and I think the work we’ve been creating strives for that type of reactivity.

IM: We are absolutely immersive, particularly in terms of language, imagination and play.

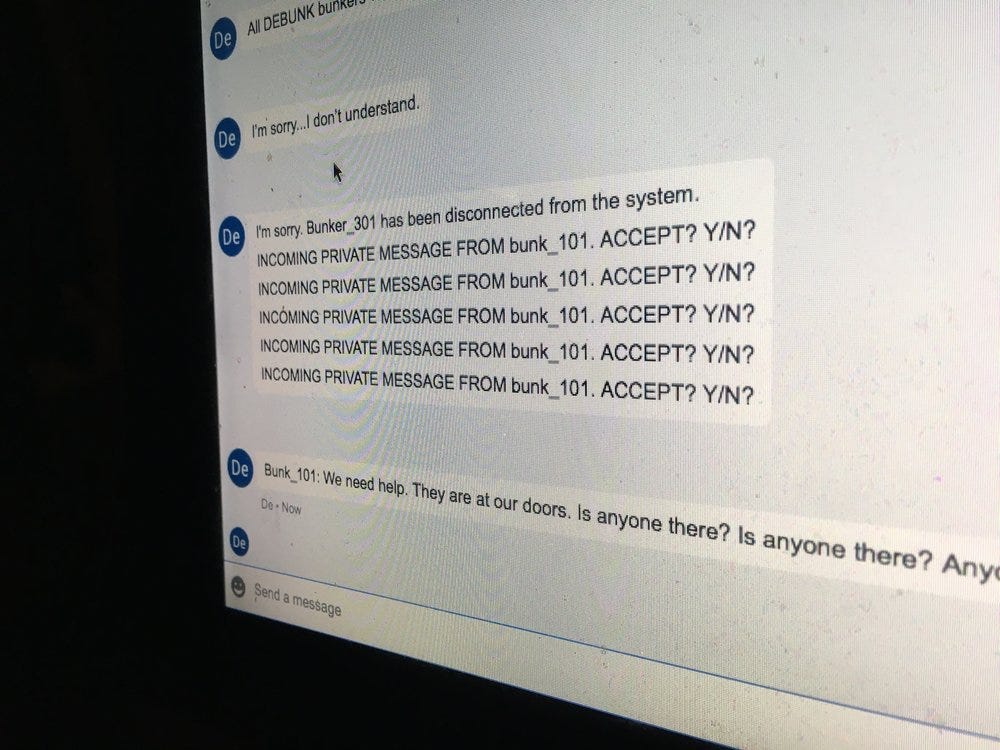

Our sci-fi choose your own adventure, The Bunker, is like the ultimate one shot D&D session: Groups of 15 make decisions that procedurally build reactive, dynamic stories and culminate in a one-of-a-kind epilogue. After a year and a half, no two endings have ever been the same.

NP: What was the moment where you knew that this kind of work was for you?

AA: I had a part in an early piece we did called The Wake. Guests would go into a darkened room and have a video conference with me through a large computer monitor. There were several different experiences that could be had, one of which was with a kind of Sesame Street-looking furry worm puppet. During the experience, the puppet would interview the guest as if they were looking to hire them as their personal assistant. The interview culminated in the guest and puppet making up a song together.

Every time I did the interview, and especially during the song, I felt like there was a real connection between the guest and myself. We were creating something together — something that wasn’t just there to be consumed or enjoyed, but that had become a unique experience that only the two of us shared.

That piece really stuck with me, and I’d like to think it stuck with the participants, and the idea of creating these really sticky, memory generating pieces, struck a powerful chord with me.

IM: In an old version of our comic book-themed immersive, Rogues Gallery, we had a performance culminate in guests spontaneously chanting, “Just one bite, just one bite,” to entice my character to eat a poison cupcake. I did.

My impromptu death made me wonder: what would happen if all our stories gave audiences that kind of broad agency?

NP: When designing — regarding your approach to presence, agency, safety, and consent — how do you cue the audience as to what’s expected of them and the nature of the content they might encounter?

Get Kathryn Yu’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

SubscribeSubscribe

IM: As a guest, there’s nothing I hate more than confusion about what interactions are intended and appropriate. Uncertainty (the bad kind) makes me feel uncomfortable, then stupid, then angry.

Guests give creators their money and time. Creators should reciprocate with clear on-ramps for how to participate and, just as importantly, roadblocks for how not to participate. Events with unclear social contracts encourage guests to make unhelpful proposals, or worse, unsafe ones.

Unsurprisingly, I am a huge fan of structure.

At the risk of sounding prescriptive, here’s a classic three-act structure we’ve used successfully in the past: teach the game systems, develop them, and then subvert them.

The first third is the hardest, requiring creators to painstakingly carve out specific, dedicated events for on-boarding. Guests must be set at ease and expectations must be streamlined. Harder still, it can’t be boring.

Once you’ve cleared the onboarding hurdle, the fun can begin: you can repeat your game mechanics in new and progressively more dynamic ways. You can take a deep dive into your story. And, ultimately, you can surrender a degree of control to your users who, by now, have been systematically prepared to wield meaningful agency, affect the story and impact one another’s experience.

AA: I know that Ian is going to talk a lot about onboarding here because A: it’s one of his favorite subjects, and B: because I have the luxury of reading what he wrote before writing my response.

For us, onboarding is all about structure, pre-planning, and design, so I’ll take the opposite tack and talk about how we approach safety, agency, and consent during the reactive parts of our experiences. I think those things are really tightly linked, agency and consent, especially during improvisational moments, because both improv and consent are about listening.

When I’m interacting with members of the audience, I’m much more focused on what they’re trying to tell me, rather than on the things that I “have” to tell them. The audience will, in my experience, be very clear about how they’re feeling — if they’re safe, happy, engaged — especially if you take the time to ask them about it.

And in the same way that interpersonal consent relies on asking questions before taking action, and respecting the answers that are given, I think highly reactive immersive events have to let the audience, in some way, know what’s coming, give them a chance to respond to what role they’d like to play in it, and then respect their decision by guiding the experience to match their responses.

I’m not saying that surprises, plot twists, or forced story outcomes can’t be done, but I think they need to be treated with a very high degree of caution. Immersive events are, for many participants, already intimidating, and I think that creators have to acknowledge that in some ways those fears are justified — part of the fun is in exploring the unknown, but that lack of control brings complications. I liken it to driving a car: I feel safest in a vehicle when I’m the one driving. I think it’s important that participants at our events feel like they have their hands on the wheel, and that they know we will respect their choice to turn, brake, or hit the gas.

NP: What works — be they creative works, books, or other inspirations — have shaped your current work?

AA: At the risk of sounding like a pretentious theatre major, I’ll say Peter Brook’s The Empty Space, because I think that at its core it’s about the indefinable energy between audience and performer, and that’s a dragon I’ve been chasing for the better part of two decades. I’ll also go with the works of Alan Moore, because I too aspire to be a wildly bearded, shamantistic, art-making misanthrope, and finish with the Disney theme parks, because those places are telling better, more engaging stories in their lines to the gift shop than half the stuff I see put out into the world.

IM: I was lucky to grow up in a home full of humor and stories. If I’ve ever game mastered for you, you probably have a good idea what it’s like to crack wise around the McNeely dinner table. Other inspirations include: Shakespeare, D&D, Star Trek and a panoply of dorky, historical-themed area control games.

The Bunker runs July 24, 25, 31 and August 1 at Wildrence; tickets are $55. Rogues Gallery runs July 26 —August 4 also at Wildrence; tickets are $65.

Read our review of The Bunker or listen to a conversation with Broken Ghost Immersives on the NoPro podcast.

NoPro is a labor of love made possible by our generous Patreon backers. Join them today!

In addition to the No Proscenium web site, our podcast, and our newsletters, you can find NoPro on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, in the Facebook community Everything Immersive, and on our Slack forum.

Office facilities provided by Thymele Arts, in Los Angeles, CA.

Discussion