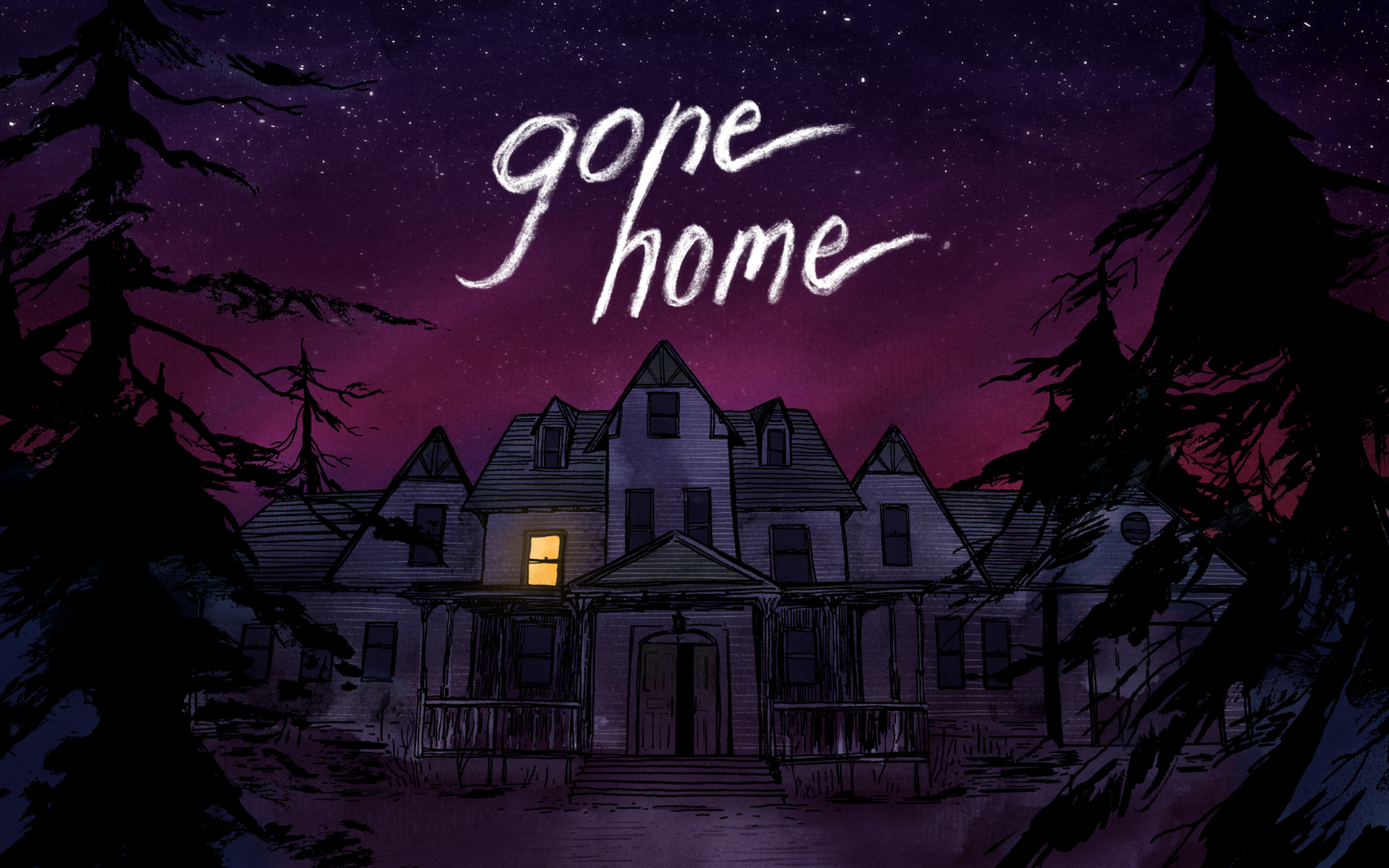

For our first deep dive into the mix of the gaming and theatrical worlds, it only made sense for me to focus on the critically-acclaimed first-person exploration game Gone Home first.

Three years ago, I booted up my MacBook, got a cup of coffee, and clicked into Gone Home for the first time. To call the game a life-changing experience would be overdoing it, but it was pretty close. Experiencing Gone Home made me realize the narrative and artistic approaches in creating games could be more engrossing and emotional than what I had previously experienced. Gaming, by its very nature, is interactive; that is what distinguishes it from any other medium: film, theatre, prose, poetry, or otherwise. For the most part, up until recently, games had squandered their artistic and narrative potential for giant stories of worlds ending, wars, diseases, and the other musings of masculine imaginations.

Gone Home taught me that gaming could transcend the Call of Duty’s of the world and tell an intimate, delicate story: one that’s personal, real, and, most importantly, emotional. This game literally changed my career path. Before this, I was on the road to becoming a traditional filmmaker. Now I’ve spent the last three years of my life studying game design and virtual reality storytelling.

At around the same time, I also noticed a similar interactive storytelling mode emerging: immersive theatre — and instantly saw a striking similarity between these two mediums.

Games, like immersive theatre, ask viewers to suspend their disbelief and enter into a fictional world, to teach and to thrill. As each form begins to define their respective tropes, I’m convinced that we can learn more from these two mediums taken together rather than categorize them as two separate forms. In this series, I want to take a deep dive into a few of these concepts — how immersive theatre can learn from Zelda, Firewatch, Bioshock, Telltale, A Bird’s Story and the Mario Brothers franchise. These games are more than pixels on a screen.

So let’s start with Gone Home.

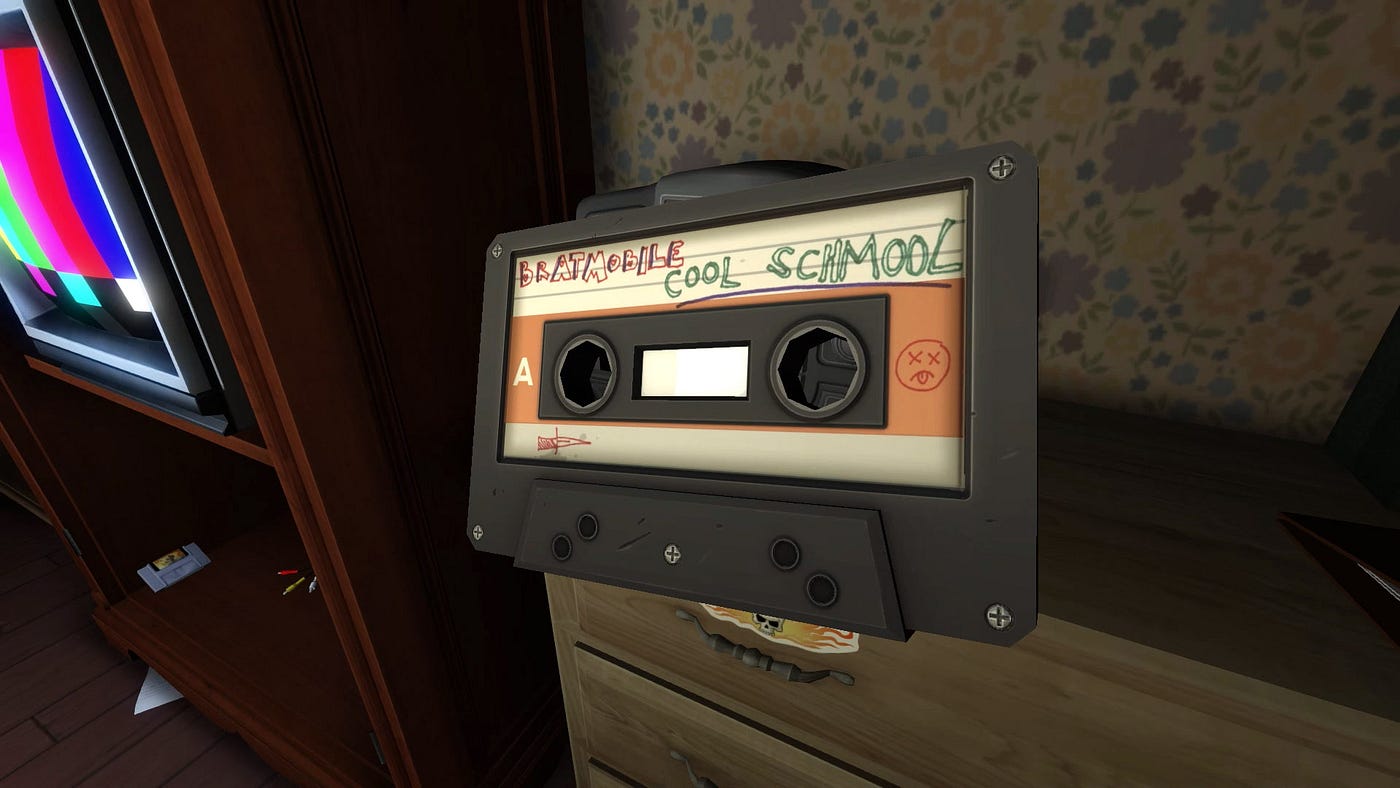

Gone Home places you into the eyes and ears of Katie — a teenage girl who has returned home from a class trip to Europe. During her year away, however, her family decided to pick up and move to an entirely new place. When you, as Katie, arrive home, instead of being welcomed into the open arms of a loving family, you’re instead greeted by a harsh rainstorm, a dark, mysterious locked house, and a note on the window, which tells you that your sister has disappeared and that you shouldn’t go looking for her.

Well, darn it. Now you have to look for her.

From this point forward, the house becomes the narrative set piece that not only expresses mood, fear, and wonder — but also becomes the primary communicator of information and story: a story that is driven entirely by place and your own curiosity.

While there are many concepts in the game that are worth visiting, I’d like to break down one big idea: Gone Home has created a modern twist on level-based game designs in order to break up a seemingly open world into smaller, digestible, and more satisfying chunks. The experience is entirely focused on telling a great story. There are no puzzles or twitch based skills to master. To ask players spend 90 minutes playing to completion, and also let them come away with an emotionally satisfying experience, the designers had to ensure that each player encountered a strong narrative within an interactive playing field.

To achieve this goal, the designers used locked doors to force a player into a narrative. While the designers do let you roam the house freely, strategically placed locked doors guide you onto their intended path. The idea of sectioning off parts of games is not a new idea. Heck, Zelda and Metroid have been using schemes like this for over 30 years. But in those instances, designers used this technique to create longer experiences with the limited memory they had on their physical game cartridges. Fans of open world games might scoff at this design choice, but Gone Home’s goal was not to provide an open, exploratory experience, but rather create a believable world to act as a backdrop for their emotional story — to create a linearity that gave users a strong three-act structure and drive them to complete the game in order to finish the story.

What does this have to do with immersive theatre, you ask? The concepts of world-building, storytelling, and three-act narrative arcs are all easily applicable to the immersive theatre genre.

An experience like Sleep No More, for example, is an open world. It gets so many of these concepts right but where it fails is storytelling. When entering the experience you’re given almost no direction, asked to walk through the experience metaphorically blind-folded, and asked to make sense of the world around you. Mind you, I loved Sleep No More. But that didn’t help me from feeling FOMO (fear of missing out) as I made any choice whatsoever. Each choice had an immense opportunity cost since, by even making a choice, I relinquished the chance to see any number of other experiences happening simultaneously.

While this may be by design (it makes you want to see it more than once to get the full experience), Sleep No More offers the audience an immense sense of anxiety and not much of a narrative for those who aren’t familiar with the source material (Macbeth, Rebecca). Every choice gives you pieces of different plots but never a single plot in its entirety.

In comparison, let’s look at The Nest, which, by its design, was very similar to Gone Home. The creators have spoken about overcoming audience FOMO and anxiety by locking certain parts of their experience into a linear order. Participants are able to get the sense that they are in a realistic, completely open world environment without having to feel like every choice causes them to miss other experiences. Moreover, designers are able to better craft the narrative into a better emotional structure — complete with an inciting incident, building and falling action, and even a climax. With these choices, the narrative experience becomes far deeper and more engrossing.

Similarly, Gone Home entices the player into a fantastically crafted world and sends them down a beautiful narrative path while quietly holding their hand the entire way. It doesn’t do any of this explicitly — but moments of organic discovery are my favorite moments in any immersive experience.

Overall, an open world mimics our natural life. It places us in a universe and asks us to make choices to craft our own narrative. I don’t know about you, but I consume stories to escape: to encounter a more perfect, romanticized version of our reality to learn something new about the human experience. You could say then that curation — the elimination of life’s white noise in favor of its more exciting parts — is the building block of creating a digestible, fulfilling story.

Gone Home simply mimicked it with some cleverly placed locked doors.

No Proscenium is a passion project made possible by our generous backers like you: join them on Patreon today!

In addition to the No Proscenium web site, our podcast, and our newsletters, you can find NoPro on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, and in our online community Everything Immersive.

Discussion