Why do we break down the fourth wall?

In proscenium theatre, an invisible, imaginary wall separates the performers from the audience: the fourth wall. In an immersive experience, this fourth wall is pierced or broken (or perhaps does not even exist in the first place).

But why do we break down the fourth wall? What is the rationale for doing so?

This is a question that should be at the center of the design of any immersive experience. But it is a question that is often glossed over or ignored despite its centrality to the “immersive” piece as a premise. As a reviewer of immersive experiences, I often find that “the tail is wagging the dog” and not the other way around. Something is designed as an “immersive” piece simply for the sake of being an “immersive” piece and not because the concept calls out for it.

To Show The Symptoms But Not the Disease

A metaphor we use often at NoPro is to say that a particular piece can have all of the “symptoms” of being fully immersive and yet lack the true underlying cause of the “sickness.” Under the tiniest bit of scrutiny, I often find that the whole is less than the sum of its parts.

Consider this scenario: if I put myself in the shoes of a theoretical creator, I ask myself:

Why do I, as a creator, wish to bring the audience into the storyworld?

What ‘purpose’ does the audience serve within this world once they are there?

How is the audience’s ‘presence’ essential to this particular piece I am creating? Why do they matter?

I have encountered many a non-proscenium piece that fails to interrogate its own reason for being — where the audience’s presence feels superfluous or glommed on. These types of shows can be well-executed, tell amazing stories, cast talented actors, and spend boatloads of money on sets, props, technology, costumes, marketing, and more. But still the question remains: once the fourth wall is gone, can you as a creator justify the audience’s existence in the world? Who are they, once they are integrated into this world? What can the audience do within the world, given that they are not brought in just to remain mute and motionless the entire time, a mere “vessel” to receive the performance? How is the piece creating conversation with the participants? Are you performing with them or at them?

Creators can always choose from a number of other equally valid forms: including but not limited to TV shows, films, podcasts, books, and more. And as the experiential marketplace becomes more crowded, answering these questions of “why?” will illuminate those rigorously designed and thoughtful immersive experiences and set them apart from the outright copycats and cash grabs.

To implicitly cast the audience member as a “ghost” or “fly on the wall” or “witness” was perhaps sufficient enough a few years ago, to treat the audience as a silent observer and nothing more. But as we enter the next decade, sophisticated audiences weaned on interactive experiences will be demanding more than mere voyeurism. Let us move then into true participation, moving into a possibility space for conversation and the potential for meaningful play.

But first: I would be remiss in not mention folks working in the field who are already taking these questions to heart, in particular those artists influenced by Woodshed Collective’s work. In Woodshed’s productions (KPOP, Empire Travel Agency), “casting the audience” is central to the immersive experience. By “casting the audience” in easy-to-understand, archetypal roles — such as party attendees, or wedding guests, or high school classmates, or members of a focus group or patients at a hospital, or new recruits to a secret cult, and so on — creators working in this vein squarely place the audience within the story world.

And, they focus on making worlds where the audience’s presence is not only easily explained and intrinsic but also essential to the experience itself. The audience may not be the star of the show, but their presence matters. These are shows in which much would be lost or even impossible to accomplish if the audience themselves were not present — the action would come to a standstill, the central dramatic question would not get answered, and more. The participants’ actions (or even refusal to act, which is a valid choice) have consequences, no matter how small, and it is acknowledged that they belong “here,” wherever your “here” happens to be.

How Does Audience-Centered Design Fit In?

Unfortunately, contemplation of how the audience fits at the center of the experience reveals fundamental flaws in certain productions that claim to be “immersive.” These sorts of experiences can cause damage to the field by incorrectly educating the audience as to what “immersive” even signifies. And indeed, it’s not easy. Using an audience-centric approach can be uncomfortable at first if you’re not used to working in interactive mediums.

At its most basic, an audience-centered approach in immersive theatre can come to life as merely allowing the audience to have agency in uncovering existing texts (as Easter eggs) within a set, or following a pre-set script and rigid decision tree, as opposed to having real influence over outcomes. Director Jamie Harper argues in a recent paper:

“As interactive and immersive forms of performance have proliferated, performance scholars have devoted increasing attention to gaming practices in order to describe the types of agency that these forms offer to their participants. This article seeks to [problematize] links that have been drawn between interactive performance and games, however, arguing that discussions of gaming in relation to performance are often limited to a textual paradigm which conceives game play as the exploratory uncovering of performance texts rather than the generative creation of emergent play narratives.”

Similarly, I argue creators must go deeper than the superficial similarities between immersive theatre and games. Felix Barrett, founder of Punchdrunk (The Drowned Man, Sleep No More), has claimed that playable shows are the future though we haven’t yet seen what his vision may produce. The field must inevitably evolve beyond the structures of looping, predetermined shows like Sleep No More where the focus has been on agency of perspective and no other kinds of agency.

But how can we accomplish this, going beyond mere mimicry of the form, when we are accustomed to using only the shallowest interpretation of the connection between theatre and games as Harper argues above? Are we stuck in a paradigm of sandbox environments with binary choices, where participants can merely hope for the occasional “on rails” one-on-one? Are we not again displaying symptoms of sickness without the underlying cause?

As the field grows and matures, I propose perhaps we can leverage player-centered and systems-focused game design methodologies to answer these difficult questions.

The Experience is The Thing

“As a game designer, you are never directly designing the behavior of your players. Instead, you are only designing the rules of the system. Because games are emergent, it is not always possible to anticipate how the rules will play out. As a game designer, you are tackling a second-order design problem….

Designers create experience, but only indirectly.”

— Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman, Rules of Play

Immersive designers face a problem similar to what Salen and Zimmerman describe in Rules of Play. Experience design is a second-order problem; the immersive experience can only be created indirectly, not directly. You can do your best to set up the underlying components of the system but you cannot control what happens in the participant’s experience; we create the situations but the participants bring them to life. So as designers, we must always expect the unexpected and prepare accordingly, starting with safety and consent, and building up to higher level topics like agency and meaningful play.

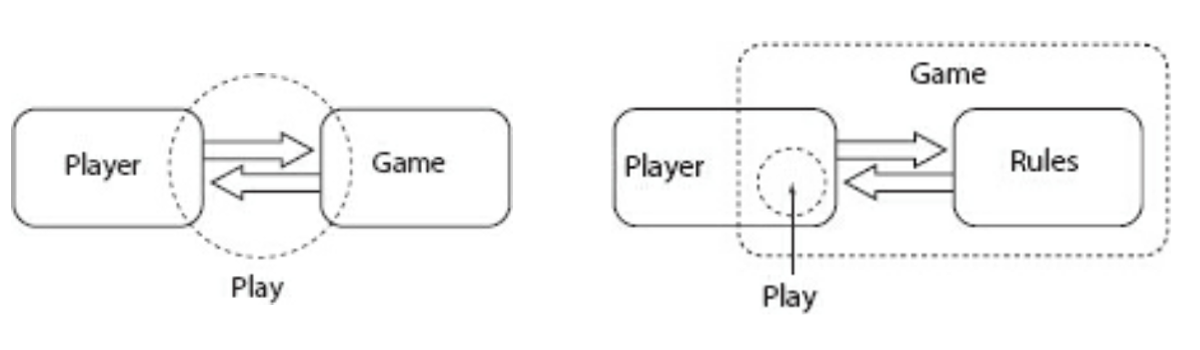

The latter two aspects are where I’ll focus next. They are areas where I believe a methodology like Situational Game Design by Brian Upton can be applied to improve upon immersive techniques that already exist. In short, situational game design is a “methodology that takes into account how play unfolds when the player either isn’t interacting or isn’t trying to win.” This is an approach that is significantly different from what many game designers are used to; it is a fundamental shift from a more traditional, transactional design approach into a philosophy that squarely places the nexus of play not within a formal system but rather within the player’s mind.

A game is therefore not a system that operates in a vacuum or an object to be consumed; it needs a participant to create “play.”

The emphasis then becomes on the thing as experienced by its players.

On Aimlessness and Stillness as Part of ‘Play’

But how exactly does this happen? Upton discusses how bursts of interactivity during an experience can be interspersed between moments of what he describes as aimlessness and stillness. It is not that the aimlessness and stillness “get in the way” of the interactive moments, like roadblocks or intros to be skipped, but that the creation of play lies inside these phases of aimlessness and stillness. This kind of “play” exists because of what the player is seeing, thinking, feeling, observing, anticipating, and interpreting. These moments of “not-moving” and “not-doing” are an intrinsic part of play itself. So perhaps those who are appear to be merely observing and stepping back may not be truly “rejecting” play.

Get Kathryn Yu’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

SubscribeSubscribe

The critical mechanic of “doing nothing” while still in the confines of the magic circle is often ignored, as notable game designer and USC Professor Tracy Fullerton observed during a recent lecture. Perhaps a game is less a series of “interesting decisions” as posited by Sid Meier (Civilization), she says, but rather a series of “meaningful situations” that players find themselves in.

Maybe participants aren’t rejecting play if they don’t appear to be “doing” anything, but rather exploring these states of “aimlessness” and “stillness” in a realized, physical environment.

So by using this more holistic and inclusive definition of play, the methodology also can help us understand the popularity of watching someone else “play,” either at home or at an arcade or on live on Twitch, or to explain the playfulness of experiencing a detailed environment or scenario on its own without necessarily interacting on the surface.

Situational game design is also by its very nature an embodied approach to the design of the interactive experience, which resonates with a lot of immersive design. And it is an approach that is closely aligned to the playfulness that is embedded in much of immersive theatre: playing to explore, playing to destroy, playing to construct, playing to experiment, and playing for story. None of these activities require a “win” state to be fulfilling and satisfying. And sometimes even the sacrifice of an individual participant can also result in a more satisfying story and experience for all (and Nordic larp has had that last one figured out for quite some time).

So: if the dominant paradigm of, say, a console-based combat game is interactivity with occasional moments of aimlessness and stillness, then can we not place immersive theatre elsewhere on that same spectrum? That is to say: the immersive work can be a container for aimlessness and stillness, with a few or perhaps even many moments of interactivity, but not necessarily leading the participant to a specific “win” state. This approach breaks through the typical stereotype of a “game” experience and aligns it most closely to other art forms like theatre, roleplaying, and more. And consequently, the act of being aimless or still during the experience perhaps even allows the participant to focus on being reflective or just present.

Context is Key

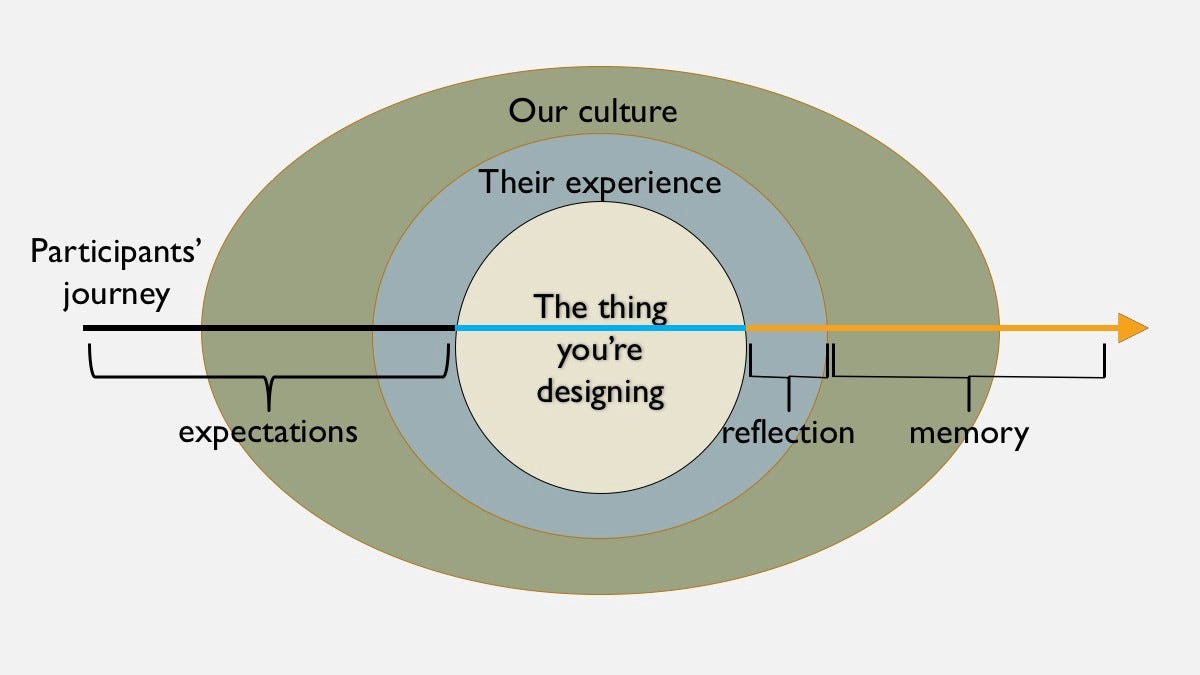

Let’s take this a step further by applying this line of thinking to the participant journey; Upton states that game’s system always “includes the attitudes, personal history, and intrinsic motivations that the player contributes to the experience.” Which has strong parallels to the experience journey created by noted larp scholar Johanna Kolnojen where the “thing you’re designing” always exists within the participant’s experience of said thing, and never outside of it, and both exist as part of a greater cultural context that participants carry with them. Humans, as we are, tend to be complicated beasts.

That is to say, as we contemplate the participant journey, we cannot view players/participants as blank slates or empty canvases for we as artists to impose our forms of expression upon, but rather their contexts will always be in conversation with the experience we’re trying to encourage or stimulate (yes, there’s that second order problem again). And all participants will enter any sort of experience with an existing context and that context is not always the same context as the creators’ context. Which is the whole point of a participant-centered approach, isn’t it? And by embracing the diversity of the participant set, we can better understand the distance between the ideal participant — who, to be frank, doesn’t exist — and the real-life, humans who trample upon any preconceived notions of the audience should react to a particular scenario. Without participants, what we build are merely “sets without people,” says immersive director Mikahel Tara Garver, a beautiful, but hollow environment, devoid of the dynamism of life.

Let us not forget that although we conceive of ourselves as simply bodies moving through space and time, those bodies carry baggage with them.

Upton takes this point further by discussing “how the distance between the game’s actual players and its assumed player can cause that system to break down.” (Italics mine.) This then is the spirit of playtesting and workshopping, is it not? A participant-centered methodology relies upon the playtest and the workshop as core to the iterative design process; designers create based upon an assumed ideal player who does not exist and then find themselves revising when faced with the diversity of the actual player population. There is no “show” without the public, as unpredictable as they are. To ignore this fact is to ignore what makes this world of ours so special.

Meaning-Making and the Live(d) Experience

There is a connection from Upton’s work in situational game design to Josephine Machon’s turn of phrase: “the live(d) experience.”

In Immersive Theatre, Intimacy and Immediacy in Contemporary Performance, Machon writes, that the phrase “‘Live(d)’ … embraces the idea of the performing and perceiving body as living, tactile and haptic material. The embodied experience underpinning immersive practice foreround this praesent exchange within the live performance moment and encompasses the fact that the human body is itself a tangibly ‘lived’ being (physiological, social, cultural, historical, political, and so on).”

Machon continues thought in further connecting the “live(d) experience” experience with meaning-making: “Immersive performance events which are stimulated by the potential human bodies have to make and interpret meanings truly expose and exploit this potential for live(d) experience.”

Upton’s writing closely mirrors this insight. He writes that:

“[Games] don’t tell us things; they allow us to perform things. And that performance is where much of the meaning of a game lies….”

And we can use situational game design as a way to deconstruct how meaning can be “constructed” during an experience.

To quote Upton again:

“Meaning consists of the strategies that the player invents in order to engage with the game. It consists of the accumulated shifts in their internal constraints [that is: predictions about how the world will unfold] that were triggered by playing.

Meaning is the residue of experience….

Meaning-making is more likely to occur when the … constraints are part of the player’s general sense of how the world works, when winning is de-emphasized, when the player is given a performative role, and when the game provides an interval of stillness in which semiotic play can unfold.”

If we then replace “game” with “experience” and “player” with “participant,” and the whole thing starts to sound a lot like…well, an immersive experience.

So to remix and revise a bit of Upton with a focus on immersive experience design:

Meaning consists of the strategies the participant creates to engage with the immersive experience.

Meaning consists of the accumulations of shifts in the participant’s thinking about how the world works.

It is more likely to occur when winning is de-emphasized, when the participant is given a performative role, and when the experience provides an interval of stillness in which play can unfold.

Meaning is the residue of experience.

So if immersive theatre is to achieve its full potential as a transformative medium, perhaps situational game design is one way to get there. The most powerful immersive encounters I’ve experienced do indeed leave a lasting “residue.” A mark on one’s soul. And, similarly, does not the best of the best of immersive theatre allow the participant a “still” space to perform or construct or co-create or curate their own experience, then encouraging new, emergent behavior? Are not the most interesting and playful moments often the serendipitous ones that don’t follow a predetermined script?

Situational game design might not be the only way forward if playable theatre is indeed the future of the form. But it is a design approach that seems closely aligned to the spirit and goals of immersive theatre. In particular, it seems aligned with the kind of immersive and interactive experiences that I want to see more of in the coming years. The kind that’s centered around the audience. The kind that takes into account the audience’s context and creates a conversation with the outside world. And the kind that thrives on emergent behaviors and allows for truly meaningful play with an infinite possibility space, or, at least, a possibility space that can grow to be bigger, much bigger than the one I encounter today.

NoPro is a labor of love made possible by our generous Patreon backers. Join them today!

In addition to the No Proscenium web site, our podcast, and our newsletters, you can find NoPro on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, in the Facebook community Everything Immersive, and on our Slack forum.

Office facilities provided by Thymele Arts, in Los Angeles, CA.

Discussion