Artist Christopher Green’s provocative satire about pornography addiction

We sit in a circle, wearing our name tags. We sip on hot herbal tea and eat gingersnaps, anxiously awaiting the start of the meeting, crumpled napkins in hand. The room is a little stuffy and too brightly lit. The chairs are arranged too closely together. Groups of two or three form small clumps, making quiet, polite conversation. Terrible New Age music plays soothingly in the background.

Hi, I’m Peter, what’s your name? Will. Hello Will, nice to meet you.

“Don’t forget to write down your expectations for tonight’s meeting on an index card and put it into the bucket placed in the middle of the room,” calls out the group leader, Chris. Place it there anonymously, of course, except everyone here can see you and there is nothing else to do while waiting, except to look around at the other people in attendance. If you briefly make eye contact with someone on the other side of the room, make sure to quickly look away.

In Prurience, audiences are invited to attend a fictional self-help group for pornography addicts much in the mold of a 12-step program (“but without the higher power stuff,” offers Chris). However, for this particular meeting, long-simmering tensions come to a boil when a newcomer, Jay, arrives and begins questioning the Prurience Method. The group leader loses control of meeting and things start to go badly, very quickly. Arguments break out, voices are raised, and bad behavior is confessed. There’s lots of foul language and graphic descriptions of pornography and many, many moments of awkward silence.

So: if you’re in New York City, and you had plans to see Prurience at the Guggenheim this week, stop right here.

Do not read any further. Reading any more of this review will spoil your experience.

And if you didn’t have plans to see this intriguing immersive work or are on the fence (and have no qualms about the subject matter or being asked to possibly participate during the show), I’d encourage you to go.

So stop reading right now and get a ticket to see it before it closes.

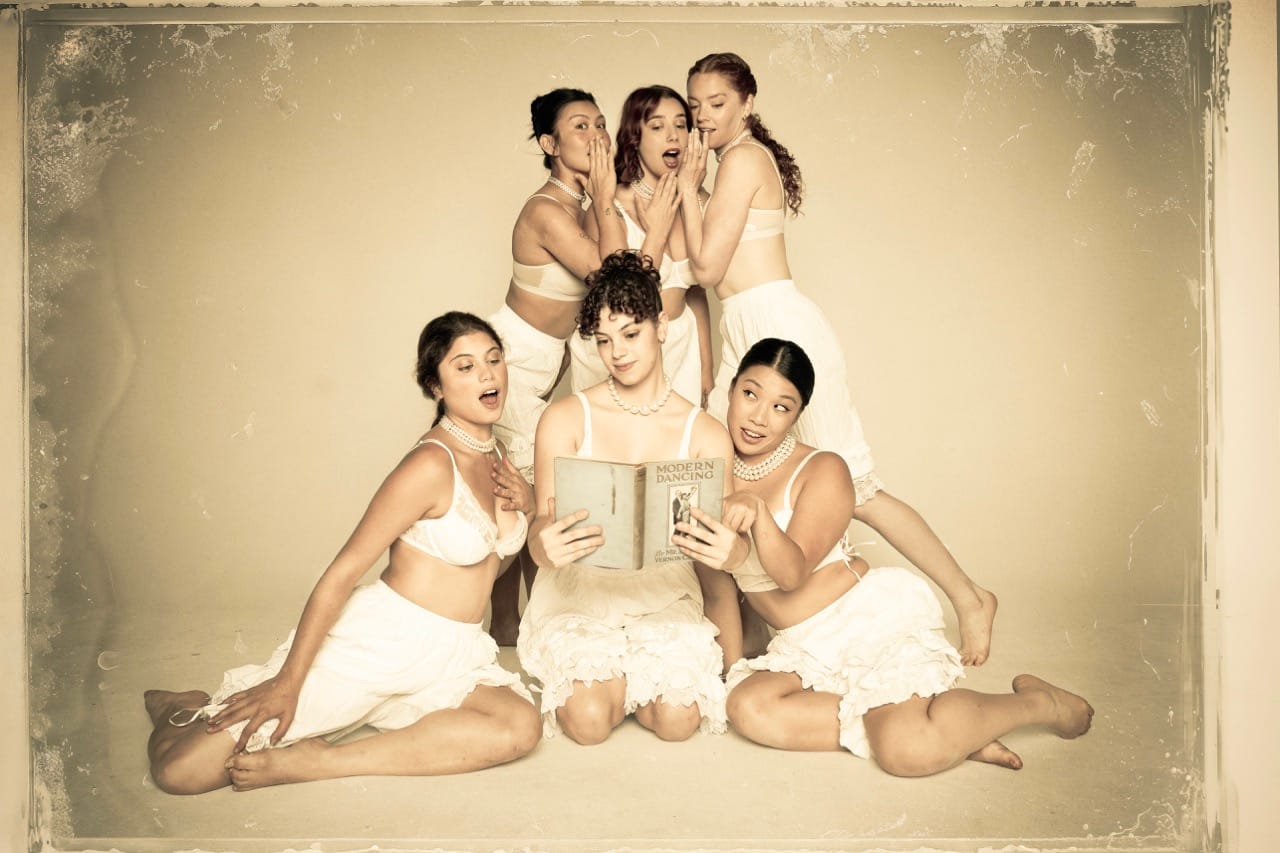

(Spoilers after the photo.)

The meeting leader (played by a soft-spoken Christopher Green), wears a white baseball cap with the group’s logo on it. He has a long braid and wears his baggy pants far too low. Chris has a creepy Cheshire Cat grin as he takes us through various ice-breaking exercises and the Prurience Method’s official song. He randomly calls on specific individuals to help with the various tasks of running the meeting (thanks to our nametags). And Chris, in fact, does a fine job of being the worst therapist of all time.

Get Kathryn Yu’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

SubscribeSubscribe

After a quiet, nervous man named Will describes an obssession with porn stemming from the age of 11 and confesses to having suicidal thoughts, Chris refuses to act, much to the horror of the newcomer Jay. His reasoning? Will has not explicitly asked for help and the Prurience Method prevents him from doing anything. Jay can’t help but express his incredulity, much to Chris’ annoyance. The rest of the group sits in stunned silence as Will wrings his hands next to me.

It becomes clear that after any serious confession or emotional outburst from a group member, all Chris can offer is a long pause and a patronizing “thank you, let’s move on,” as the Prurience Method’s philsophy is “never to guide but to walk side-by-side” with their members. Obvious cries for help are consistently ignored and the only thing Chris seems to be good at is hawking the Prurience Method’s DVDs and CDs and playing us videos of the method’s founder, a former porn star turned into corporate talking head, offering only meaningless platitudes. (The man next to me scoffs quietly as we watch; I begin to suspect he’s an actor.)

Prurience is not a show just about pornography addiction and whether or not the affliction even exists, but also a satire around the commercialization of the self-help industry and the stigma of mental illness in today’s society. What use is telling people to “get help” if the quality of the assistance is unregulated and unproven? Just who are these self-help gurus anyway? How exactly is a former adult film star qualified to help with an addiction disorder? Who is Chris and why is he the leader of the meeting, anyway?

About halfway through the session, the attendees of the meeting are called upon to add their thoughts to the posterboard “feedback tree” during a five minute break. I see someone has scrawled “you are not helpful” and another person has written “this is bullshit.” It’s hard to tell which notes are coming from the characters and which are coming from other attendees. Chris chooses not to address any of the feedback.

Later in the meeting, a distraught group member, Brian, confesses to driving his lover away because he feels compelled to watch porn even when an attractive young man is in bed with him. He’s standing a few feet away, describing explicit sex acts, and then, in a moment of vulnerability, asks for a simple hug. There’s another long, awkward pause before someone gets up from their chair. Chris, tellingly, stays motionless. (I’m unclear as to whether the giver of the hug is another actor, or an audience member. I think it’s an actor. Maybe.)

In many shows reliant upon audience participation, it’s fairly easy to distinguish plants from the actual members of the audience. They are those who are slightly too eager to be called upon. When asked a difficult question, their responses are always a little bit too forthcoming, too rehearsed. When two plants begin to argue with one another, over the heads of the audience, the drama often feels forced and unnatural. Prurience sees this, acknowledges the issues, and blasts right through it. And in this self-help group setting, it’s often quite difficult to identify who is a plant and who isn’t. Is “Porno Jim” telling his actual true life story or is he playing a character? Why is “Ellie” so eager to share that she loves gay porn?Are we in a real meeting? Is this a piece of theatre? Does it even matter? And just when I think it’s clear who’s an actor and who isn’t, the entire enterprise gets turned on its head.

Someone sitting quietly becomes visibly uncomfortable during an especially heated exchange. She finally asks Chris, “Is this real? Or made-up?” I’m afraid she’s going to walk out. Then Chris responds in a completely unexpected way, ripping apart the previous hour of fiction.

Things turn upside down. And then upside down again.

Prurience is messy, ambitious, hilarious, and bewildering. The play can overwhelm and lose focus at times. (Spoiler alert, again.) It’s a work where nothing happens. No one is rescued, healed, or saved. No one seems to have learned any valuable lessons. There’s a lot of soul-baring. A lot of yelling. A lot of skepticism. Bona fide audience members are mistaken for actors (it turns out the hugger was indeed a spectator). Those assumed to be audience members turn out to be well-placed plants in the crowd. Prurience raises questions about porn, capitalism, consumption, social media, and addiction that it can’t truly answer. And it pulls the rug out from under us once, and then again, becoming a meta-play by the end. But for fans of the interactive and immersive theatre genre, it’s utterly compelling.

Prurience continues at the Wright at the Guggenheim through March 31 (dark Thursdays). Tickets are $40–45. Please note this show contains explicit sexual references, discusses suicide, and may feature other sensitive content.

No Proscenium is a labor of love made possible by our generous backers like you: join them on Patreon today or the tip the author of this article directly on Gumroad:

In addition to the No Proscenium web site, our podcast, and our newsletters, you can find NoPro on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, in our online community Everything Immersive, and in our Slack forum.

Discussion