[The following contains spoilers, of a sort, for Third Rail Projects’ The Grand Paradise.]

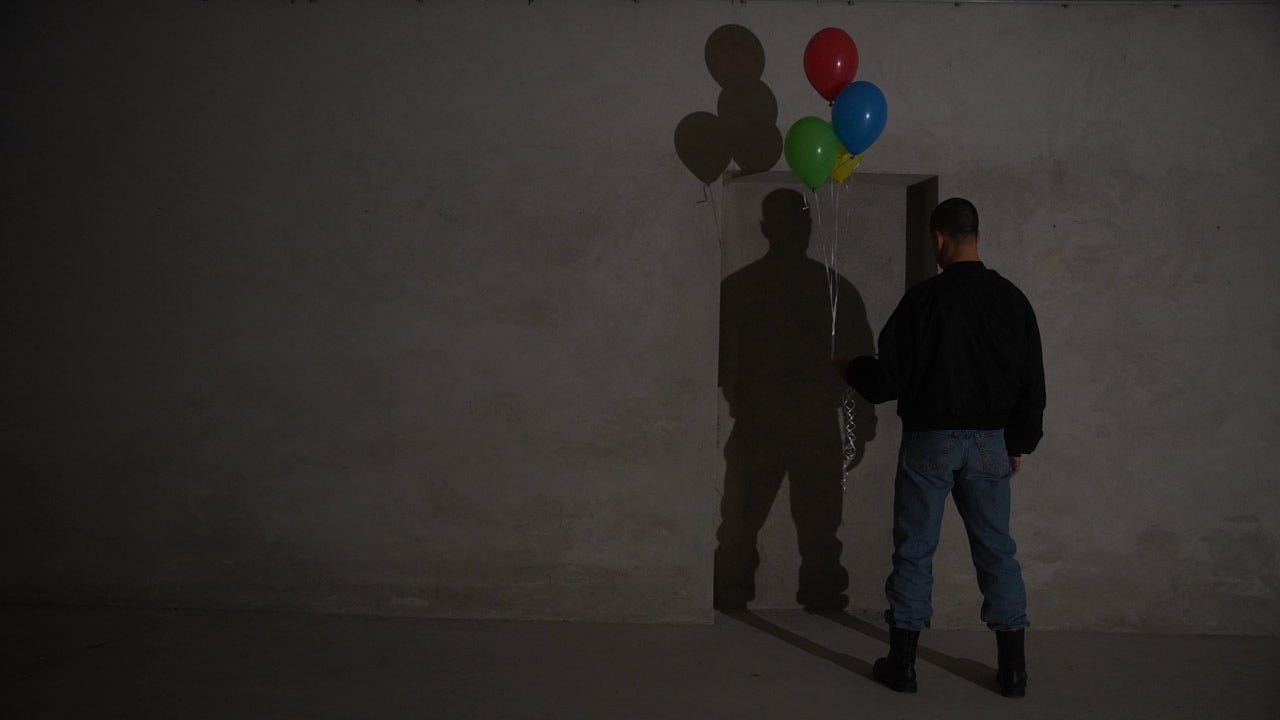

Can you be nostalgic for a place that doesn’t really exist? For a moment that never really happened?

This is not a question that I thought I’d be asking myself on the L train at midnight. I had come to Bushwick seeking the promise of paradise and left with an existential crisis.

Now that we’ve started at the end, we can skip to the beginning. Not that time is really playing fair with us here.

The Grand Paradise is the latest large-scale immersive work from New York City’s Third Rail Projects. That’s the company behind the long-running Then She Fell, among whose rabid fans I count myself a member. Sleep No More put immersive theatre on the cultural map, but for a good number of us it is the more intimate Then She Fell — which uses characters from Alice in Wonderland to map out an emotional landscape of frustrated desires — that initiated us into the deeper mysteries of immersive.

When Third Rail announced that they were working on a new, bigger show in Brooklyn last year I knew that I’d have to make pilgrimage. When the theme was set as a 70’s-era island resort that may or may not possess the fountain of youth I wasn’t really sure what to make of it. Flashes of the old Fantasy Island TV series danced through my mind, leaving questions of just how much of a story such a piece was going to be able to generate. Or if that was the aim at all.

So I left LA for Brooklyn equal parts skeptical, faithful, and anxious. Would it be good? Would it make sense? Would I like it? These are not necessarily the same questions.

I avoided reviews, even steering clear of everything but our own Zay Amsbury’s notes on the show, which clearly seeped down into my unconscious. Other than that I wanted to go in as cold as possible. The frame of mind one hits an immersive with can be just as important as the material itself, and expectations are a huge part of that game.

In typical fashion, I was the first to arrive at the door that night, and at house open made my way into the small lobby of the venue. For this show it has been decked out as a plane boarding gate circa 1979. Here the audience is corralled before being shepherded behind a curtain, shown an orientation video, and then allowed access to the titular Grand Paradise’s main courtyard. There’s not much in the way of narrative in the lobby, although a tiny detail here and there can act as a skeleton key as to what is about to come next.

Now this should be the part where I take you through a recap of the narrative of the show, and offer up some notes about the relative strength of that compared to other immersive works. But I’m not going to do that. Other reviewers have done that. Some have found that the production comes up short on these grounds.

That is, in a large part, because The Grand Paradise isn’t a piece of theatre.

It is a work of high magic. A ritual exploration of death and desire. A series of encounters and meditations designed to suspend the normal flow of time.

To be sure: there are characters in this piece whose story arcs it is possible to follow. Like other pieces of immersive theatre there are enough “tracks” in The Grand Paradise that multiple viewings are needed to get a handle on the stories that are being told about them. But those stories, much like the disco and Fleetwood Mac vibe, is an act of misdirection.

For the first half of The Grand Paradise I was still squarely in the “skeptical” stage. I’ve been to more than my share of immersive theatre productions at this point. Enough that I’ve begun to catalog the back of tricks that artists have at their disposal to initiate their audiences into the worlds that they are trying to build.

For instance: each guest to the Paradise is greeted, Hawaii-style, with a lei. This is true both for the patrons and the lead characters whose arcs we are invited to follow. The lei has multiple functions. On a practical level, it is used to mark who has and hasn’t had an initiatory one-on-one experience. It also serves as a kind of sympathetic magical connection between the audience and our protagonists. In fact, that connection blurs the line: is the family of five whose sexual awakenings we are going to be both witnesses and accomplices to the protagonists of this piece or is the audience? Is it both? The answer to that question is how emotionally invested you end up.

Paradise is a honey trap. The performers who make up the permanent residents of The Grand Paradise seem to resonate with a dangerous, seductive energy. There were moments when the audience was all assembled in the courtyard and the cast watched us from above, that I felt like we were being watched by birds of prey. Hungry ghosts in need of our repressed desires.

But dread is not the order of the night, even if it is part of the palate at hand.

The twin poles of death and desire create a high dynamic range of possibilities.

On my first visit, I found myself on a track that involved a couple of encounters with one of the Disco Girls (Lauren Muraski). Late in that cycle she brought me into a small bedroom — I’ll spare the tiny details here, so as to not ruin all possible surprises. What I will note is that it is a special kind of torture to have a ridiculously alluring dancer lay down in bed with you and trace lines on your palm. To possess the knowledge that with a turn of your head you could kiss them, and that pretty much every part of your reptilian brain is screaming at you to do so.

I wonder, actually, if some folks make the attempt. It’s a dangerous game. The ethicist in me curdles at the thought of what could go wrong while the mystic in me laughs in delight at how much of a therapeutic mindfuck this is for the right participant. Knowing that this is make-believe, even with my senses insisting that it was not, I stayed in a passive role and let the scene run its course with her firmly in the driver’s seat. At its heights immersive theatre is a partner dance, one where the audience does not know the steps, best to follow the performer’s lead.

With our duet done the Disco Girl led me into a vestibule where she had stashed another patron. I proceed to listen to them play out a version of the same scene. Then something I’ve never experienced in a piece of art — of any kind — before happened: I found myself deeply jealous. What had transpired in the scene had, gently, torn open some old scars. As I sat in the little vestibule with an Atari 2600 and Fleetwood Mac LPs the blood of those wounds seeped out. I recalled all the times I had blown an opportunity — or thought I had blown an opportunity — with a beloved.

And in that room I could hear…him. With her. The little voice in my head that told me it was just a show was drowned out by the sensation of the copy of Rumors in my hands. Of the traces of her fingers on mine. Of the memory of the last time I was that close to someone I loved. Of all the moments like that which ever were, and the sudden fear that this simulacrum would be the last. It’s only make-believe. But then again, how different are all those lost “real” moments from the pretend one that just happened.

Then they were done. The door reopened. He and I were both on our way.

What had been stirred up remained. When I left the venue that night I made my way up the street to Union Pizza Works and ate like I had just undergone a break-up. Word to the wise: the chocolate mousse really helps with that feeling. Wine, pasta, and chocolate were not enough to wash the wound away. It is what haunted me on the L that night: that sense that there was a moment lost in time, waiting for me in this other place. A conviction that I had to get back to Paradise somehow.

Luckily all it really took was clearing some time on the schedule and buying another ticket. Which is what I did. Three nights later I was back in that place…and let’s tackle that right now.

One of the reasons why theatre folk had trouble parsing Third Rail Project’ latest production is because they’ve built more of a place than a performance. The clue is right there in the title. The show isn’t titled Then She Fell or Sexytime Family Vacation Shenanigans It is called named after the place. This is not a condemnation of the performance skills of the company. Quite the contrary. On the whole, the cast does such a damn good job of crafting experiences that convey theme and tone that the borders of narrative dissolve.

Do the characters in a story know that they are in a story? The audience does, but what happens when the audience becomes the soul-doubles of the protagonists? Are we able to know that we are in a story?

A second tour of Paradise revealed the way that the company deployed archetypes in the storylines of the family members in order to provide a framework for the alchemy of desire. I was able to catch payoffs of scenes that I had witnessed the first time, and setups I had missed. My intent was to stay on a different path, but one of the issues with The Grand Paradise is that leaning into the sandbox form — literally in the case of the beach room — creates a paradoxical lack of control over what an audience member can witness. The mechanism of the show is hidden in the chaos of the middle sequence when the doors of the space are open. Tracks are still unfolding but what threads lead where is impossible to discern. Once the doors close again fate will have its way with you.

I was determined to beat fate. I was determined to see something new while the doors were open.

And then the Disco Girl, Lauren Muraski, was standing next to me in the courtyard.

I didn’t know she was going to be in that night’s cast. One part of me didn’t want her to be. Another desperately did. We made eye contact. She took my hand. I turned away, looking up at the dance that was unfolding. I anticipated being pulled away, into some side space. I didn’t let my imagination go further. Then I felt her let go. She disappeared into the chaos. I didn’t follow. I wondered if I should have. I wondered if she had marked me. Or if she had failed to mark me before approaching, and then found herself holding hands with a creeper. This is why I had wanted to avoid her: I didn’t want to break the spell of what had happened before, even as I wanted to test my luck. Now I was worried that I spooked her. Or had I missed out on something by turning away?

So I let it go. Followed a tip someone gave me to get on a different track for the second act. The first scenes were new and revelatory. Elements that I had inferred about the nature of this place, about the themes that were being explored, were explicitly confirmed through a sequence of encounters and monologues that moved me in a different emotional direction from my first visit.

Then they led me back to the disco. At the start of the track that had led me into the bedroom. The scene was unfolding again. Only from a different angle — because of where I stood.

Then she was in front of me again. The Disco Girl. With her predatory gaze. She held her hand open and I gave her mine. She pulled me into a back room I hadn’t seen before. She would pause to cut me with one of her intense stares. Stopped to pick up a drinking vessel that I recognized from another scene. One that held a potent magical function in the mechanisms of Paradise. I followed her to a door, marked Exit. She paused. My heart hammered. Without trying, I’d broken the social contract. My presence was a violation. I’d failed because deep down inside I was chasing a feeling I wasn’t supposed to have.

She opened the door. I braced myself for my ejection from Paradise.

And we were back in the disco.

She was back on track. I was back to the wall. I hadn’t broken the contract. That was all in my head. Like the idea that I’d missed a one-on-one earlier. Or that she had flitted away after recognizing me. Or that she had recognized me at all. Our connection was an illusion. A spectacularly crafted illusion. A commentary on the elusive and imagination fueled dynamics of desire. There was nothing beyond those moments. No room in the back where fantasy collides with reality. There never is. Nor is the fantasy any less glorious for being just fantasy. Freed from the constraints of our “real” world.

From a certain point of view, everything is in our heads, and this is the phenomenon that Third Rail Projects is playing with in The Grand Paradise.

The assemblage of techniques that Third Rail Projects uses to craft this effect pretty much includes the entire immersive playbook: dance, storytelling, spectacle, seduction, poetry, “easter egg” set design, and an oblique attack angle on narrative. For this production, the storytelling chops of the cast end up carrying a lot of the thematic weight, more than I expected going into the space. I ended up being reminded that there is a vast difference between an actor reciting a monologue and a person telling a story.

I had the pleasure of seeing Katrina Reid deliver the same story on both nights, and what struck me was that she was able to make this piece — complete with some eyelet interactions in the form of questions which colored the telling — feel fresh each time. Then I heard her rendition of a piece near the end of my second run that had a quality of connection which had been lacking during my first visit when delivered by another actor. These encounters are leading me to believe that storytelling trumps the traditional monologue in intimate theatrical settings.

Recitation and declamation are still a trap, and I’ve seen that happen more than once, but there’s a tenor to a story being told one-to-one (or one-to-few) that is far different from even a good revelatory monologue.

The Grand Paradise, however, is not without flaws.

The trickiest part of the whole shebang is the scale of what is being attempted. A few score audience members winding their way through encounters both open and directed onto tracks is a logistical challenge in and of itself. The structure of the show favors a loose, observational stance for the audience for the first half. This left me feeling disconnected from events on my first view. Uninitiated into the mysteries, I couldn’t really make sense of what was going on. But as the night went on Paradise — clearly — worked its charms on me.

Perhaps there is no quick and easy way to bootstrap someone into a great immersive. It takes time to shed expectations and your day-to-day skin. To become acclimated to the social compact of an ambitious immersive. This seems even harder with a piece that thematically is not as easy to like as it is to love.

Much of my early time in The Grand Paradise was spent being aware of both the production’s ambitions and the veil that seemed to be between me and the reality they were constructing. It felt as if the company was reaching towards something and, for a long stretch, I feared that we could not get there together.

Once we did, however, it was far different from what I thought I might find. Or perhaps it is a more honest version of what I sought. I went looking for a summer fling, and what I got were all the bittersweet memories that come from the thoughts of what might have been.

Which, I believe, is the point. Side by side with the secure knowledge that those moments are still there, in time. Suspended in the amber of memory and ecstasy. Always waiting for us. In a grand paradise.

The Grand Paradise is scheduled to close on May 29th. Escape while you can.

Discussion